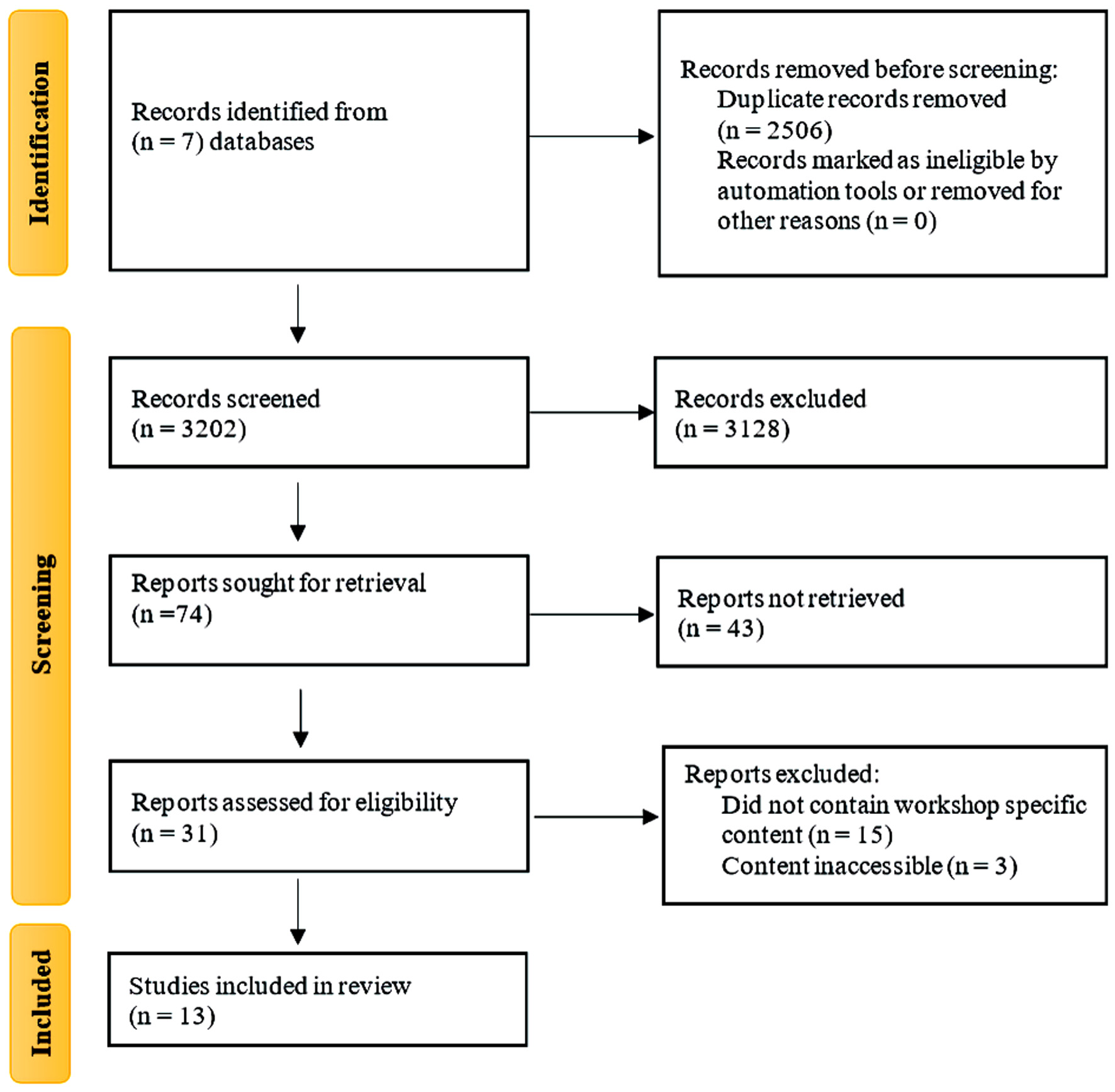

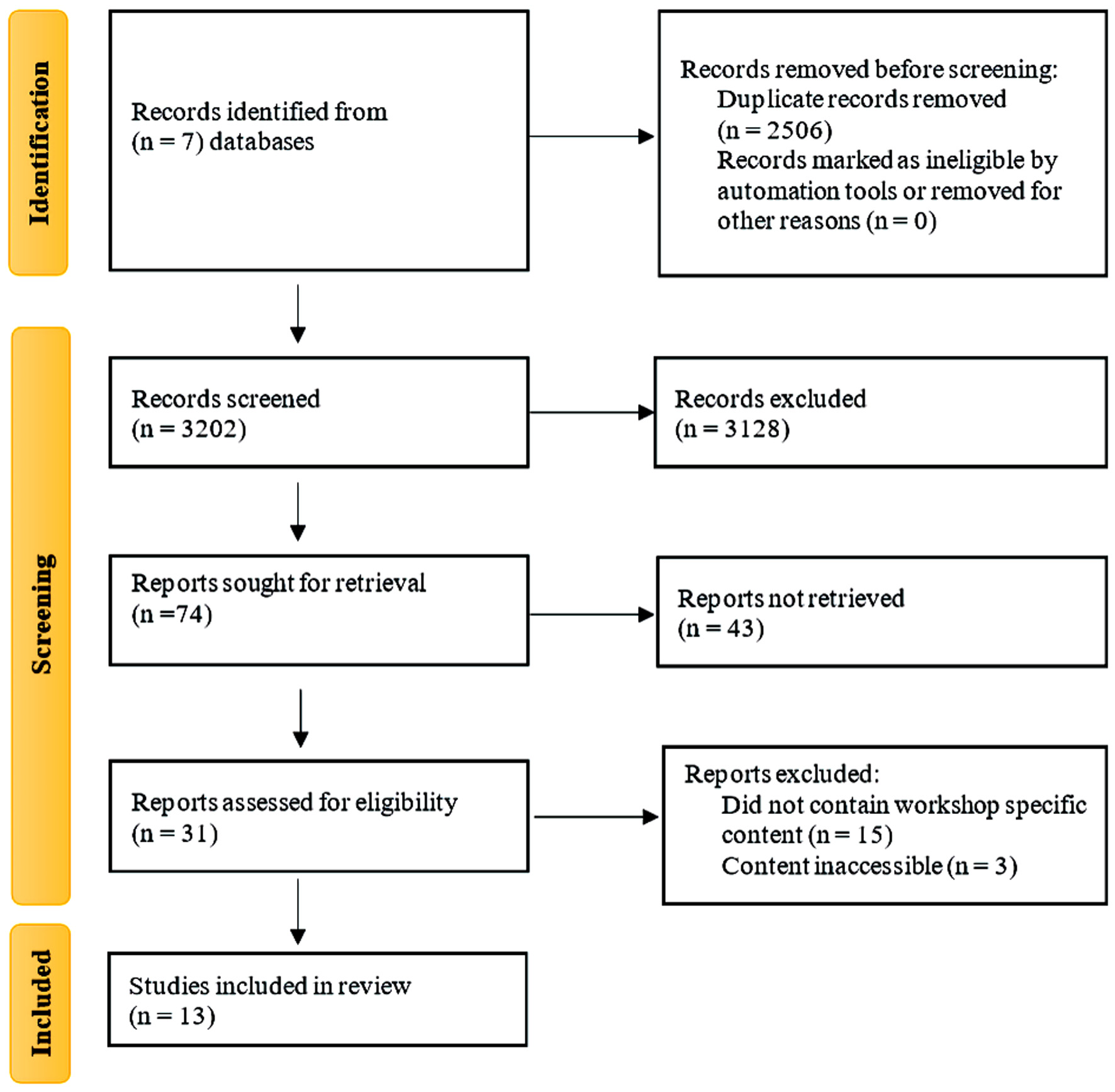

Figure 1. Search process, returns, and curation for youth neuroscience outreach literature.

| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.neurores.org |

Short Communication

Volume 12, Number 2, August 2022, pages 76-91

Toward Health Equity in Neuroscience: Current Resources and Considerations for Culturally Broadening Educational Curricula

Figure

Tables

| Publication | Population (used for analysis) | Training format | Duration | Content | Assessment format | Reported outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies are presented in the order described in the text. Arrows indicate statistically significant effects reported by authors. STEM: science, technology, engineering and math. | ||||||

| MacNabb et al, 2006 [21] | Grade 5-8 students from Minnesota (n = 9,023) Grade 5-8 teachers from Minnesota (n = 56) University of Minnesota | Teacher training Presentations Exhibit stations Class activities/experiments Various resources loaned to classrooms | 2-week BrainU sessions 3-day workshop | Nervous system anatomy Neuronal communication Movement Genetics and behavior Visual influence on motor learning and neural pathways Neural pathways Learning and memory | Short multiple-choice survey Open-ended feedback survey for students | ↑ in understanding of neuroscience concepts by teachers and students ↑ in teacher confidence in teaching neuroscience ↑ in students’ interest in neuroscience ↓ in the number of inappropriate or negative peer interactions |

| Saravanapandian et al., 2019 [22] (same workshop as Romero-Calderon et al, 2012 [29]) | Grade K-12 students across the Los Angeles area (n = 298) University of California, Los Angeles Undergraduate students (n = 29) | Student training (2 weeks) Practice presentation to peers (1 week) Practice presentation to peers and faculty (1 week) Visiting K-12 classrooms (5 weeks) | 10-week program 4/10 weeks used for preparation | Training in the 5E (engage, explore, explain, elaborate and evaluate) instructional model | Pre-workshop surveys Post-workshop surveys 1 week after completion 3 - 6 multiple choice questions on key learning objectives | ↑ in teaching from undergraduate students ↑ confidence in communicating science and ↑ in interest in pursuing teaching careers ↑ in K-12 students’ STEM interest and understanding of neuroscience concepts |

| de Lacalle et al, 2012 [23] | Grade K-12 students in California | Kids Judge! science fair Mentoring program “Medicine in Movies” film series | Autumn 2006 - Spring 2011 | Biomedical sciences (including predominantly the neurosciences), with a focus on scientific discovery | Teacher surveys Focus groups Science communication survey Attendee surveys Interviews with program staff Performance data on the California Standards Tests (CST) | ↑ in proficiency rates over the project period ↑ in community engagement Small ↑ in attitudes towards public speaking Undergraduate confidence in their ability to present science to children did not change much due to prior experiences Classroom teachers and mentors reported that the mentoring program was valuable to students |

| Deal et al, 2014 [24] | Local K-12 students (n = 3,500) from Biddeford, ME Undergraduate (n = 45) and graduate/professional students (n = 33) from the University of New England’s Center for Excellence in the Neurosciences | Modules focused on different topics with age-appropriate activities 8 - 10 students per group | 60-min time-adjustable modules | Brain safety Neuroanatomy Drugs, abuse, and addiction Neurological and psychiatric disorders Cognitive function | Student survey using “My Attitudes Towards Science” (MATS) survey Feedback survey for undergraduate student volunteers | ↑ connections between undergraduate volunteers with university faculty ↑ in confidence presenting scientific information ↑ in interest for careers in the scientific field |

| Vollbrecht et al, 2019 [25] | Grade 6-8 students from underrepresented groups in the Holland, Michigan area (n = 174) Hope College undergraduate students (n = 22) | Discussion Short introductory presentation Demonstrations Activities | 5-slide PowerPoint presentation followed by post-test 2 - 7 days after classroom visit | Content modified from BrainLink curriculum [21] | 10-question multiple choice quiz (pre and post workshop) to assess student understanding Survey on the impact of the outreach event for undergraduate students | ↑ in understanding of neuroscience concepts ↑ in excitement and ↑ in confidence in science communication in undergraduate students No significant change was observed for questions 2, 4, 8, or 10 |

| Brown et al, 2019 [26] | Preschool students from Northwestern PA ages 5 - 6 (n = 18) Undergraduates studying neuroscience or education | Lessons were designed and taught by two undergraduates Introductory neuroscience lesson Individual check-ins 5 lessons with activities | 3-h sessions 3 days a week for 6 weeks | Anatomy and function Sensory and motor systems Brain plasticity and learning | Baseline assessment Post-workshop assessment | ↑ in percentage of correct quiz answers ↑ in performance on post-assessment test questions in students who received neuroscience outreach lessons compared to control students |

| Toledo et al, 2020 [27] | Low-income grade 6 students in Riverside County (n = 77) | Tiered curriculum Interactive lessons | 1-h weekly workshops for 5 weeks | Neurons Brain anatomy Autonomic nervous system function Drug effects | 15-min pre and post workshop survey Demographics Attitudes towards science and learning Understanding of neuroscience concepts | Significant ↑ in attitudes towards science and learning ↑ in knowledge post-intervention in 7 out of 8 content areas No changes in excitement about learning science material and school learning opportunities No changes in knowledge of neurons, which was unexpectedly high at pre-test No statistically significant gender differences were found |

| Bravo-Rivera et al, 2018 [28] | K-12 schools (n = 20) and universities (n = 17) in Puerto Rico | Series of individual outreach workshops Hands-on activities | Not specified | Understanding neuroscience in journal articles Basic neuroscience concepts (e.g., anatomy, neurons, function) Use of “Backyard Brains” laboratory equipment | None | None |

| Romero-Calderon et al, 2012 [29] | Grade K-5 (ages 5 - 10) (n = 958) Grade 6-8 (ages 11 - 13) (n = 415) Grade 9-12 (ages 14 - 18) (479) Multi-level schools grade K-8 (ages 5 - 13) (n = 61) University of California Los Angeles | Introductory presentation Age-appropriate in-depth presentations Hands-on activities guided by undergraduate students | 45-min workshops during the 2006 - 2011 school years | Basic neuroscience concepts Senses, memory and learning, motor systems and reflexes, and brain injury (ages 5 - 9) Sleep and dreaming, handedness, and pain (ages 10 - 13) Drugs, nerve impulse conduction, gender differences, circadian rhythms, stroke, and neurodegenerative diseases (ages 14 - 18) | None | None |

| Pollock et al, 2017 [30] | Underserved high school students in the Bay area Local high school and a local youth center | Combination of game-making and neuroscience education | Weekly, 2-h after-school sessions over the course of 2 academic quarters | Modified curriculum using the California State University East Bay (CSUEB) Game Jam and Brain Bee Engineering and science portion based on the California Next Generation Science and Engineering Standards | Event maps and analysis of activities and guidance format Video data (23 sessions) Observation and field notes (15 sessions) | ↑ in engagement in neuroscience when integrated fully into game design The experience affords students rich, engaging opportunities |

| Fitzakerley et al, 2013 [31] | Grade 4-6 students in Minnesota | Short introduction Interactive demonstrations Real human brain activities | 45 - 60-min interactive presentations | Structure and function Electrical and chemical communication Learning and plasticity Neuron anatomy | Teacher survey on value of presentations and teaching experience Student survey on attitudes towards science, views of scientists, and their own ability to learn | ↑ in attitudes towards science ↑ in understanding and memory of neuroscience content |

| Colon-Rodriguez et al, 2019 [32] | Puerto Rican minority high school students (n = 200) Undergraduate students (n = 424) | 4 workshop sessions Discussions and activities designed by University of Michigan graduate students (n = 9) Spanish/English workbook | 8-h sessions | Central nervous system Sensory, motor, and autonomic systems Common neurodegenerative diseases Anatomy | 15-min pre- and post-workshop evaluations (11 questions both multiple choice and short answer) Written feedback form | ↑ in understanding of neuroscience and enthusiasm towards science in both high school and undergraduate students Workshop topics and hands-on experiments most well received |

| Chudler et al, 2018 [33] | Grade 6-8 students at Washington State or Oregon schools (n = 1,240) Middle school science teachers at Washington State or Oregon schools (n = 23) | Professional development workshops in either Seattle (5 shorter days) or Yakima (3 days) 5E model (engagement, exploration, explanation, elaboration, and evaluation) Individual lessons on different topics | 8 lessons + resources given to teachers to administer over the course of 12 weeks | Neuroanatomy and neurophysiology Effects of plants on treating illness and altering brain function Movement and motor functioning Neurodegenerative diseases and neurological disorders Exploration of bacteria and its relationship to neurological diseases Stem cells and regeneration Stimulants and depressants Nervous system | Pre- and post-tests 15 content-related questions Attitudes about science were measured using a subset of questions from the Simpson-Troost Attitude Questionnaire (STAQ) | ↑ in percentage of correctly answered content questions for all grades (54.1% average correct answers compared to 69.3%) Number of correct science content answers did not vary significantly based on gender Differences between average pretest score and posttest score varied by grade level No statistically significant change in the Self-Directed Effort scale or the Science is Fun for Me scale Motivating Science Class scores were higher at post-test but not statistically significant |

| Publication | Population | Indigenization approaches | Assessment | Reported observations and outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies are presented in the order described in the text. Arrows indicate statistically significant effects reported by authors. STEM: science, technology, engineering and math. PBE: Place-based education. | ||||

| Cheeptham et al, 2020 [34] | 13 - 15 years old Indigenous youths that attended the Thompson Rivers University (TRU)_ Aboriginal Youth Summer Camp in Science and Health Science (n = 149) | Exposing campers to science and health science through academic, recreational, and culturally-relevant camp activities Place-based education (PBE) via guided tours of local facilities (water treatment plant, rural First Nations health center) Interactions with professionals in healthcare to explore potential career paths Partnerships with local community | Exit surveys, wrap-up evaluation and debriefs with staff Informal conversations with campers and other participants | ↑ in attendance rates ↑ in levels of stated interest and growth over time |

| Thomas et al, 2006 [35] | Literature review, interviews (n = 15) Participants in research (n = 6) | Combined healing properties of Aboriginal healing circles and self-awareness and empowerment practices of the psychotherapy technique known as “focusing” | 45-min interview to discuss purpose of research Self-reporting mental health assessment | Reported themes from participants’ first-hand experiences were experience, relationships, spirituality and connectedness, empowerment, and self-awareness ↑ in student interest when content acknowledges existing frameworks of healing and knowledge within Aboriginal communities Further efforts are needed to equip First Nation practitioners with knowledge, values, and skills required to promote holistic wellness within their families and communities |

| Ragoonaden et al, 2017 [36] | Students taking EDUC 104, a new collaborative Indigenous perspectives course at the University of British Columbia-Okanagan 11 women and 6 men between ages of 18 and 56 (n = 17) | Holistic approach from Indigenous epistemology Medicine wheel with four dimensions of learning: wisdom and logic (mental), illumination and enlightenment (spiritual), trust and innocence (emotional), and introspection and insight (physical) | Interviews conducted at the conclusion of the course Longitudinal, mixed-methods study | Interviews yielded three major themes: circles of learning, peer mentoring, and relationship with the instructor The interconnectedness of the self in relationship to society and education is important to ↑ student learning |

| Higgins et al, 2019 [37] | Opinion text | Indigenous ways-of-knowing-and-being Place-based education (PBE) Collaboration with Indigenous scholars, Elders, and Knowledge Keepers | Not applicable | Marginalization results from the attempt to fit Indigenous knowledge into Western scientific knowledge frameworks Indigenous ways-of-knowing-and-being are often included as tokenistic means to an end Fairclough’s three-tiered model is effective in allowing conceptualization of different relationships involved in curriculum document production |

| Mack et al, 2012 [38] | Individuals from Native communities across the USA Individuals running informal programs to engage Native American youth in science and environmental education (n = 21) | Indigenous ways of knowing Evaluating progress in spiritual and ethical terms Integrating Native science (e.g., medical plant uses, cosmology, and star knowledge) Two-eyed seeing | Interviews | Confirming and validating traditional knowledge using contemporary science is a way of conducting culturally sensitive science education programs Tailoring educational programs to a community’s specific local culture and needs leads to an ↑ in effectiveness Native ways of knowing can add value and ↑ academic success for Indigenous youth Effective practices include creating hands-on, inquiry-based lessons that are reflective of the culture; utilizing the community as an integral resource in the development of curriculum; using local Native language. |

| Fellner, 2018 [39] | Author reflection and opinion text | Implementing Indigenous protocols and ethics, talking circles, storytelling, and land-based pedagogies as integral parts of the learning process Delivering curriculum using oral teachings and storytelling Inviting Elders to deliver curriculum Delivering curriculum on the land and/or in the context of community ceremonies and events Using traditional medicines | Talking circles | Incorporating Indigenous knowledge, and introducing students to how to bring Indigenous ethics, standards, and practices into their work is essential for decolonizing curricula Students learned how to prioritize community and ceremonial protocols and ways of knowing, being, and doing in their work. Learning Indigenous knowledges in relation to community wellness is critical for students in community psychology and allied disciplines, as “our communities know what we need to heal”. |

| Root et al, 2019 [40] | Students enrolled in MIKM 2701 at Cape Breton University | Course led by local Elders and Knowledge Keepers with facilitation support from university faculty Provided culturally relevant education by introducing Mi’kmaw-centered teaching and learning processes grounded in the locally specific contexts of Unama’ki (Cape Breton) and Mi’kma’ki Two-eyed seeing Course began and ended with traditional ceremonial prayer | Assessment in the form of self-reflection analyses by students at week 13 of taking the course | Analysis yielded five themes: identifying cultural self (situating); msit no’kmaq or relating to others and the natural environment; feeling or experiencing and acknowledging the emotions raised through learning; responding through shifting; and/or, sticking in personal position Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students expressed satisfaction about information shared during the course ↑ in knowledge of Indigenous storytelling, spiritual ceremonies, and accounts of residential school experiences from personal, Indigenous perspectives for non-Indigenous students Indigenous students indicated that they had never learned about their culture, language, and history in their school experiences. |

| Farrell et al, 2020 [41] | Teachers along the Fraser Canyon corridor, in the Nlaka’pamux and Sto:lo Nations (n = 35) | Adapting Place-Based Education (PBE) and decolonizing education for the instructor and researchers | Used a “what + how = value” basic equation | PBE is necessitated by active, living relationships in place and provides opportunities for critical pedagogy grounded in Indigeneity. ↑ in ability of pre-service teachers to apply historical and geographic thinking competencies and build principled practical knowledge of PBE Walking the land gave context and ↑ in understanding to students’ learning. |

| Pearce et al, 2005 [42] | Students at Mother Earths Children’s Charter School in Canada (MECCS) Over 300 students, teachers, parents, community Elders, and researchers | Approach is delivered in a cultural context and framed around respect for Mother Earth, respect for all living things, and respect for oneself (PBE) Medicine wheel informs the school philosophy Interactive learning activities that focus on a holistic, visual, and team approach to education Daily routines incorporate fundamental Indigenous practices such as prayer, sweetgrass ceremonies, sharing circles, and healing circles Involvement of Elders | Visual narrative inquiry to directly evaluate the experiences of students, parents/guardians, teachers, admin, and Elders Focus on the individual and how life might be understood through a telling and re-telling of the visual narrative story | ↑ in focus on respect in the school rather than authoritarian discipline ↑ in harmony, cooperation, and group work due to the cohesive, community-oriented environment ↑ in school year with longer school days allows for seasonal ceremonies that occur at times outside of regular school days |

| Brown et al, 2020 [43] | Unspecified | Talking circles | Literature review Case study using talking circles to assess community engagement | Talking circles are useful to build/nurture/reinforce/heal relationships, and connect spiritually/intellectually/emotionally with other people Talking circles can be used as an evaluation practice for evaluators looking to build relationships, share power, and solve problems |

| Bartlett et al, 2012 [44] | Mi’kmaw community of Eskasoni First Nation Unspecified adults (those attending post-secondary) | Two-eyed seeing | Discussion on Integrative Science undergraduate program created to include Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing into an established science university program | Mainstream and Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing must engage in a co-learning journey Two-eyed seeing is central to co-learning Development of an advisory council of willing, knowledgeable stakeholders is needed to implement such changes |

| LaFever, 2017 [45] | Unspecified | Medicine wheel Talking circles | Literature review | Using all four quadrants of the medicine wheel is a step all educators can take to Indigenize pedagogy |

| Baydala et al, 2009 [46] | Indigenous children (K-8) from North Central Alberta (Cree, Nakota Sioux, Blood, Blackfoot, Ojibway, Dene, Inuit, Metis) | Medicine wheel | Longitudinal evaluation of change in measures of behavior, academic achievement, self-perception, and health of children in the form of questionnaires | All measures significantly declined or showed no significant change Higher performing students transferred out of the school and ↑ in enrolment of special-needs students. |

| Neeganagwegin, 2020 [47] | Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers Indigenous youth in school | Indigenous educational models PBE Use of the native language Focus on relationships | Interviews | Incorporating Indigenous educational models into Canadian schooling is beneficial for Indigenous populations and for educators and governments who work with Indigenous communities. |

| Future Skills Centre (FSC- CCF), 2020 [48] | Elementary and secondary students, Indigenous learners in post-secondary education STEM graduates | Indigenous science approach Emphasis on relationship to space and time Structural authority Two-eyed seeing | Literature review | Bridging Indigenous ways of knowing with Western science leads to an ↑ in engagement and performance for Indigenous students. ↑ in motivation and enrolment in STEM when specialized programs targeted to Indigenous students is used Other strategies include curriculum reform for K-12, increase in STEM outreach to Indigenous students, and creation of associations for Indigenous professionals in STEM occupations. |

| Science First Peoples, 2019 (teacher resource guide) [49] | Elementary and high school Indigenous students | Incorporation of Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous Science PBE Interconnectedness | Teacher resource guide on how to structure curriculum | Resource guide promotes the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives in science courses. |

| Preston et al, 2013 [50] | Aboriginal high school students in Saskatchewan | Inclusion of Aboriginal worldview Medicine wheel teachings on focusing on mind/body/emotion/spirit | Semi-structured individual interviews | ↑ in motivation for educational success stemmed from 4 quadrants of learning: awareness (east, physical, fire); knowledge (south, mental, earth); continuous improvement (west, emotional, water); and perseverance (north, spiritual, air) Incorporating features of Aboriginal pedagogy when teaching can ↑ student engagement |

| Rebeiz et al, 2017 [51] | Aboriginal youth (First Nations and Metis) | Land-based learning (PBE) Incorporation of spirituality Medicine wheel | Case study of the H’a H’a Tumxulaux Outdoor Education Program | ↑ in student engagement and learning when land-based learning focused on hands-on experiences, guided by traditional spiritual values and built upon the medicine wheel is used |