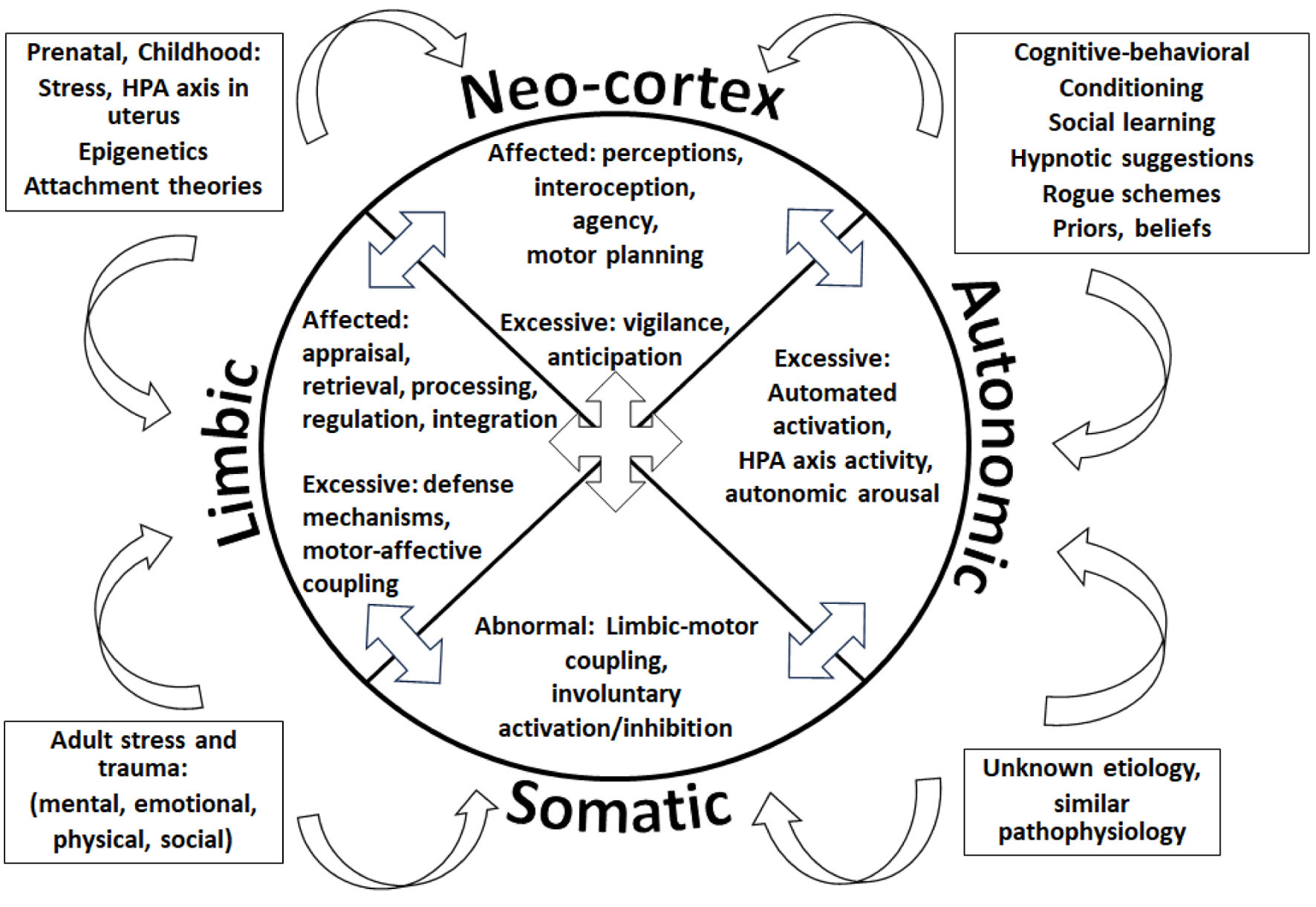

| Patient demonstrates apprehension about FND recovery | Emotional appraisal | Cognition influences emotional responses | “What past events have shaped this emotional response?” Increases patient’s awareness about emotional appraisal. |

| Emotional retrieval | Recollection of emotionally charged memories | “Tell me about other moments when you have felt that way.” Biographical assessment, practices emotional retrieval, allows the exploration of further networks as stated below. |

| Patient becomes restless and fidgety | Sensorimotor-affective coupling | Physical sensations linked to emotional states | “As you recall those memories and emotions, what are you noticing in your body?” Creates awareness about the link between sensations and emotions, practices interoception, allows exploration of further networks. |

| Interoception | Noticing internal sensations | |

| Patient’s movements continue, tapping the right leg, rubbing the hands together. There is mild facial flushing and sweating. | Autonomic activation | Activation of the ANS | “I notice that your energy level and movements have increased, are you sensing that too?” Practices interoception, brings awareness to emotional-motor connections, involuntary motor activation linked to emotions and memories, creates opportunity for autonomic self-assessment and regulation. |

| Limbic-motor coupling | Linking emotions to motor functions | |

| Involuntary activation of motor pathways | Survival responses to protect against adverse, stressful situations | |

| The patient states “I am feeling strange right now” | Defense mechanisms | Reduce uncomfortable internal experiences. | “Tell me more about this strange feeling? How does it feel? Where is it? What is it telling you?” Practices interoception, explores defense mechanisms, making sense of the patient’s experience, uniting mind-body. |