| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.neurores.org |

Case Report

Volume 7, Number 1-2, April 2017, pages 13-15

Relevance of Early Diagnosis in Reactivated Acute Nervous Form of Chagas Disease: Importance of Cytology in Cerebrospinal Fluid

Anabela Angela Gabriela Angeleria, b, Florencia Luciana Mauroa, Fernando Guerraa, Luis Alberto Palaoroa, Adriana Esther Rochera

aUniversidad de Buenos Aires, Departamento de Bioquimica Clinica, Laboratorio de Citologia - INFIBIOC-C.A.B.A., Argentina

bCorresponding Author: Anabela Angeleri, Adela Celia Burgos 41: ingeniero Pablo Nogues, C/P: 1613, Provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina

Manuscript accepted for publication February 22, 2017

Short title: Early Diagnosis in of Chagas Disease

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jnr416w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

The presence of trypomastigote Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi) was detected in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of an immunosuppressed patient, due to AIDS, and diagnosed as reactivated acute nervous form of Chagas disease. We consider the importance of the cytological study of these kinds of smears in immunosuppressed patients who present focal neurological lesions as the early diagnosis of this condition, mainly to reduce the high mortality ratio that it has.

Keywords: Trypomastigote; T. cruzi; CSF

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Chagas disease, or American trypanosomiasis, is a chronic and systemic disease, caused by a unicellular parasite called Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi). It is recognized by WHO as one of the 13 tropical diseases most unattended worldwide, and by the Organizacion Panamerica de la Salud, as a poverty disease [1, 2].

T. cruzi is found in vertebrates’ blood as trypomastigote, which is extremely mobile and has one flagellum. In tissues, the parasite changes to amastigote, capable to persist in this way for many years [3].

There are many ways to transmit T. cruzi, according to the region being endemic or not. In endemic regions (South America and part of Central America), the most common is the vectorial way. The vector insect, Triatoma infestans, popular called “vinchuca”, can share the man’s environment. This is the most important species in the South, and when this insect stings a person, it can defecate on him, and if the person scratches, the infecting forms of T. cruzi in the feces penetrate the skin and move to the blood torrent. In no endemic zones, other transmission ways prevail: transfusion, organ transplant, and congenital [4]. Nowadays, a new way is proposed: by syringe in intravenous drug users (IDUs) [5, 6].

Specially for the AIDS emergency in 1981, and other minor immunosuppression forms, a new face of this disease has appeared: reactivated acute nervous form in immunosuppressed patients [7].

The main form of presentation of this reactivation is due to the affection of central nervous system (CNS), and in second place, the heart. The CNS symptoms are characterized by focal lesions (Chagomas) in first place, or diffuse meningoencephalitis in second place. The Chagoma lesions could be indistinguishable from other tumor lesions also found in this kind of patients with immunosuppression (neurotoxoplasmosis, primary CNS tumors, lymphoma and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy) [8].

Cytology of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a very sensible and specific method in the diagnosis of several diseases. Among them, the reactivated acute nervous form of Chagas disease is found, in which it is possible to observe mobile T. cruzi parasite in a fresh smear [9-11].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A male patient from Jujuy, Argentina (endemic zone for Chagas disease), carpenter of 74 years old, weighing 78 kg and 1.83 m tall, says to live in Buenos Aires (no endemic zone) from 1973 but he refers he had lived in contact with vinchucas during his days in Jujuy.

Medical background included tuberculosis (TB) at the age of 23, pyloric ulcer, prostatectomy due to benign prostatic hyperplasia, and hemorrhoids.

On December 3, 2016, he went to the Clinical Hospital Jose de San Martin, presenting with asthenia, adynamia, weight lost (30 kg), night sweats, dry cough, fever and dyspnea, and for these reasons, he was internalized. The patient referred all these symptoms since 9 months to the present, getting worse the last two. He also had oral candidiasis. Because of the background, it was considered the TB, and a bacilloscopy looking for acid-alcohol bacteria was made, with Zihel-Neelsen stain. The result was negative. An ELISA was made for HIV, being positive, which was confirmed by Western blot, resulting in an LT CD4+ cells of 105/µL by flow cytometry.

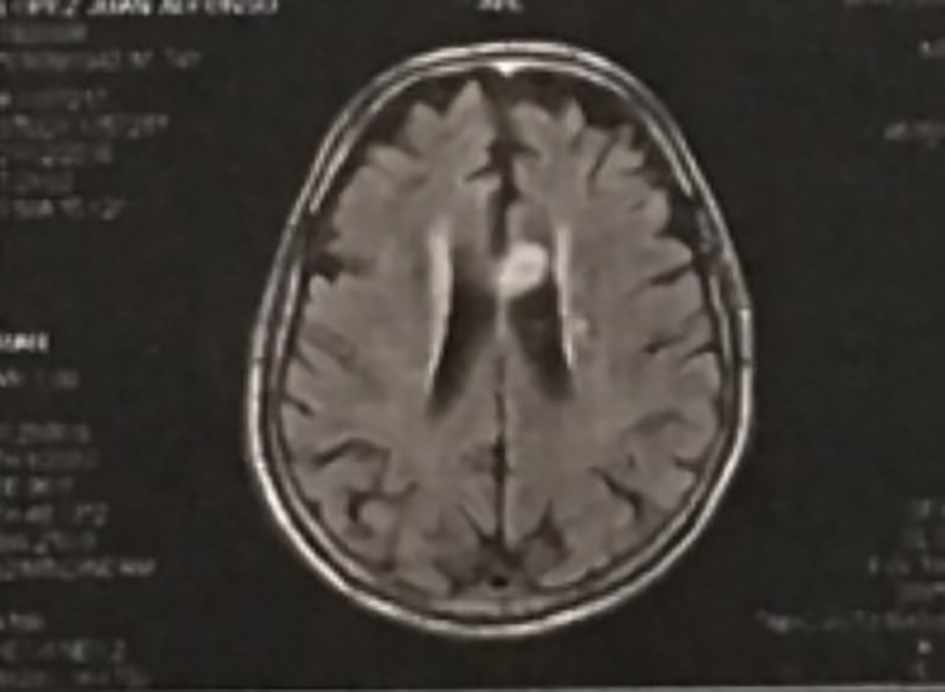

During internalization, the patient suddenly presented right faciobraquiocrural hemiparesis, aphasia, sphincters relaxation, and isochoric pupils. This outbreak was considered as a stroke, for which a magnetic resonance (MR) was preformed, showing a localized mass in the frontal hasta of the left lateral ventricle (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Brain magnetic resonance imaging showing a frontal mass located in the left lateral ventricle. |

Due to immunosuppression produced by AIDS and the mass found, toxoplasmosis was suspected, because it is one of the most common complications in these patients, which even can produce encephalon focal lesions. Therefore, empiric treatment was initiated, using pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine.

Later, serological studies were made searching for citomegalovirus: IgG (+) IgM (-); Epstein-Barr: IgG (+) IgM (-); hepatitis B: Ag HBs (-), HBs antibodies (surface) (-) HBc antibodies (core) (-); Toxoplasma gondii: IgG (+) IgM (-); and VDRL: non-reactive. Chagas antibodies (+) using two methods (indirect hemagglutination and chemiluminescence). Strout technique which looks for T. cruzi trypomastigotes in blood tested positive.

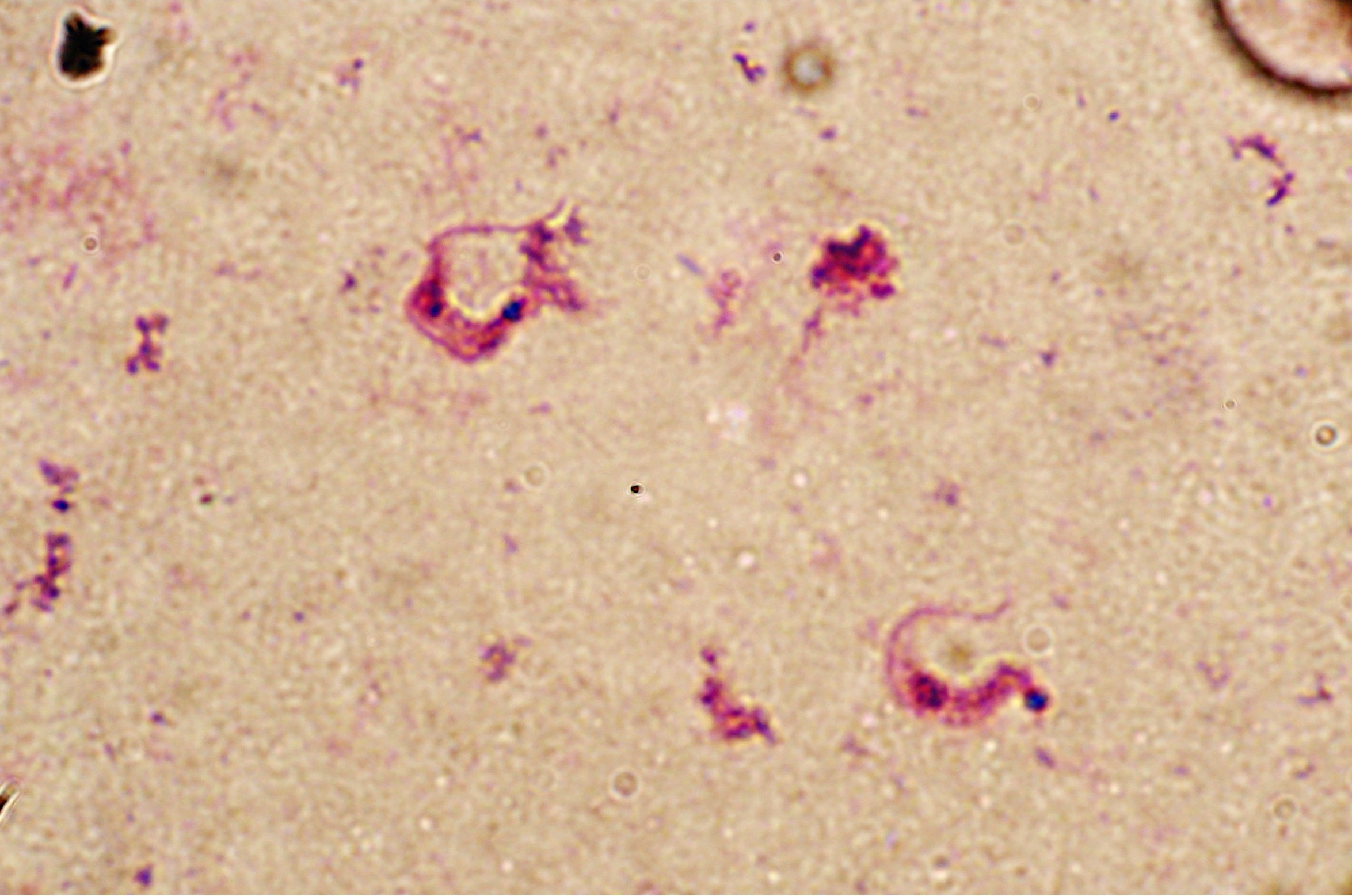

On further days, the patient got worse, showing sensory impairment, and a lumbar puncture was performed. The CSF was remitted to the cytology lab, where the presence of mobile trypomastigotes was observed, in the fresh smear under the optical microscope, without staining (Fig. 2). The liquid was centrifuged during 10 min at 250 g, and was stained with 1/10 diluited Giemsa during 5 min. The cellular count was 5 cells/mm3, predominating lymphocyte cells; the chemical assay revealed glucose 0.40 g/L, proteins 0.69 g/L and chlorine 110.9 mEq/L.

Click for large image | Figure 2. T. cruzi triphostigote in CSF. Giemsa stain × 1000. |

A few days later, a CT scan was done, showing cerebral edema (Fig. 3). Due to the presence of the parasite on CSF, the anti-toxoplasma treatment was suspended, and the patient was treated as a reactivated Chagas disease, using benznidazole.

Click for large image | Figure 3. CT scan showing cerebral edema. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The clinical manifestations and the image studies are not pathognomonic of cerebral Chagoma in patients with reactivated acute nervous form [8]. Serological study is important to the diagnosis of Chagas disease, but in some patients presenting extreme immunosuppression or also intravenous drugs-addicts (first they get HIV and then are infected with T. cruzi by sharing syringes), serology could be negative [6, 12, 13].

Clinical consensus for managing AIDS patients presenting focal cerebral lesions is, initially, an empiric anti-toxoplasmosis therapy, followed by CT scan after 7- 14 days [14]. If there is no answer, it is indicated to proceed to biopsy the brain searching for T. cruzi amastygotes.

The long term to diagnose Chagasic encephalopathy and therefore, the delay in the implementation of its treatment, is one of the most important factors that contribute to its high mortality ratio, which is over 79% with a life expectancy of 21 days [5].

CSF cytology presents a sensitivity of 85% to detect T. cruzi trypomastigotes [5]. Unlike biopsy, this technique is less invasive, simpler and the results can be obtained in a few hours.

Searching for T. cruzi trypomastigotes in CSF should be done in all immunosuppressed patients with an LT CD4+ lower than 200/µL, presenting focal neurological lesions, or signs of meningoencephalitis, with or without positive Chagas serology, and/or had been lived in endemic zone.

Studying CSF by cytology is a high sensitive technique, and also a very valuable tool at the moment of diagnosis of a reactivated Chagas disease form, contributing to diminishing the high mortality ratio that these patients have.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

| References | ▴Top |

- Rassi A, Jr., Rassi A, Marin-Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet. 2010;375(9723):1388-1402.

doi - Hotez PJ, Molyneux DH, Fenwick A, Kumaresan J, Sachs SE, Sachs JD, Savioli L. Control of neglected tropical diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(10):1018-1027.

doi pubmed - Rassi A, Rassi A Jr, Rassi SG, et al. Doenca de Chagas. In: Lopes AC, ed. Tratado de clinica medica, 2nd edn. Sao Paulo: Editora Roca, 2009: p. 4123-4134.

- Torrico F, Alonso-Vega C, Suarez E, Rodriguez P, Torrico MC, Dramaix M, Truyens C, et al. Maternal Trypanosoma cruzi infection, pregnancy outcome, morbidity, and mortality of congenitally infected and non-infected newborns in Bolivia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70(2):201-209.

pubmed - Cordova E, Boschi A, Ambrosioni J, Cudos C, Corti M. Reactivation of Chagas disease with central nervous system involvement in HIV-infected patients in Argentina, 1992-2007. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12(6):587-592.

doi pubmed - Sergio R. Auger, Ruben Storino, Miguel de Rosa, Oscar Caravellio, Maria I. Gonzalez, Edgardo Botaro, Liliana Bonelli, Oscar Rossini. Chagas y SIDA, la importancia dl diagnostico precoz. Rev Argent Cardiol. 2005;73:439-445.

- Pittella JE. Central nervous system involvement in Chagas disease: a hundred-year-old history. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103(10):973-978.

doi pubmed - Lazo JE, Meneses AC, Rocha A, Frenkel JK, Marquez JO, Chapadeiro E, Lopes ER. [Toxoplasmic and chagasic meningoencephalitis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: anatomopathologic and tomographic differential diagnosis]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1998;31(2):163-171.

doi pubmed - Menghi CI, Gatta CL, Arcavi M. [Trypanosoma cruzi in the cerebrospinal fluid of an AIDS patient]. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2010;42(2):142.

pubmed - Carlos B. Ramirez, Alejandro Jaramillo, Antonio Becerra Gomez, Enrique Monsalve Vargas, Wilson Villarreal Cantillo, Rafael Villabona Lun. Chagas's disease as cerebral massy. The first case reported in Colombia. Acta Neurol Colomb. 2007;23(1).

- Tte. Cor. MC Jose Antonio Frias Salcedo, Subtte. QFB Norma Angelica Moreno Hernandez, Cap. 1º. Pas. Med. Esther de la Cruz Acevedo. Trypanosomiasis cerebral en VIH/Sida. Reporte de un caso y revision de la literatura. ENF INF MICROBIOL. 2006;26(4):123-128.

- Silva N, O'Bryan L, Medeiros E, Holand H, Suleiman J, de Mendonca JS, Patronas N, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi meningoencephalitis in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999;20(4):342-349.

doi pubmed - Corti M, Trione N, Corbera K, Vivas C. [Chagas disease: another cause of cerebral mass occurring in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2000;18(4):194-196.

pubmed - Ferreira MS, Borges AS. Some aspects of protozoan infections in immunocompromised patients- a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97(4):443-457.

doi

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.