| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.neurores.org |

Original Article

Volume 12, Number 2, August 2022, pages 69-75

Urban Indigenous Experiences of Living With Early-Onset Dementia: A Qualitative Study in Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Meagan Odya, d, Cathryn Rodriguesa, Parkash Banwaitb, Lynden Crowshoea, Rita Hendersona, Elaine Boylinga, Cheryl Barnabeb, c, Pamela Roacha

aDepartment of Family Medicine, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB T2N 4N1, Canada

bDepartment of Community Health Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB T2N 4N1, Canada

cDepartment of Medicine, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB T2N 4N1, Canada

dCorresponding Author: Meagan Ody, Department of Family Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB T2N 4N1, Canada

Manuscript submitted November 24, 2021, accepted January 26, 2022, published online February 24, 2022

Short title: Indigenous Experiences of EOD

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jnr713

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: The aim of the study was to build understanding about the lived urban Indigenous experiences of early-onset dementia (EOD) to inform health services planning.

Methods: A phenomenological qualitative pilot study completed with a total of five participants recruited and interviewed for 30 - 60 min. Interviews were transcribed using NVivo12 software and thematically coded with a multi-step process.

Results: Four overarching themes were identified: urban Indigenous understandings of living with EOD, Indigenous family experiences of adjusting to EOD, western approaches to healing and thriving with EOD, and Indigenous ways of healing and thriving with EOD.

Conclusions: The findings of this project provide better understandings of urban Indigenous experiences of EOD and also dementia more broadly. Through a better understanding of the Indigenous experiences of dementia, urban healthcare providers can be more aware of the needs of urban Indigenous people living with dementia, and specifically EOD, and may face and plan to co-design health services accordingly.

Keywords: Dementia; Indigenous health; Qualitative research; Early-onset dementia

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Early-onset dementia (EOD) is used to describe a group of symptoms that affects the memory and cognitive ability of individuals diagnosed under the age of 65 years old [1]. Individuals living with EOD face different challenges and issues because their social constructs and social responsibilities are different than individuals living with dementia over the age of 65 [2]. Individuals with EOD may have spouses/partners, older parents and younger children that are still dependent on them [2]. If they are still employed, an individual with EOD can begin to experience changes in work performance which can negatively affect their self-esteem as a valued worker of the community and provider for their family [3]. An EOD diagnosis often also has a profound effect on the loss of identity for the individual and creates feelings of social isolation [4]. EOD accounts for approximately 6% of all dementia diagnoses and is often overlooked for service and policy development and provision [5]. Currently, most dementia resources available are designed for the population over the age of 65 and there is a paucity of information regarding the experiences of younger people with dementia and the experiences of their families.

Furthermore, there is little published or grey literature to provide understanding about the burden of lived Indigenous experiences of dementia in general, including EOD. In the Canadian context, Indigenous people refer to the descendants of the first peoples of this land and include three groups: First Nations (FN), Metis, and Inuit. Based on current population-level data, dementia is a healthcare priority for Indigenous populations in Canada as the age-standardized prevalence of dementia in FN persons is 34% higher than in non-FN individuals in Alberta [6]. This trend is evidenced in other countries where Indigenous populations continue to experience the legacy of colonization; in Australia, the incidence rate ratio of dementia for Indigenous males and females between the ages of 45 and 64 years is 27.3 cases per 1,000 person-years in comparison to the non-Indigenous population where it is 10.7 cases per 1,000 person-years [7]. However, detailed information on the needs of Indigenous people living with dementia, and those of their families and communities, remains sparse.

As community connection is a key part of many Indigenous cultures [8-10], positive support from community members plays an important role in the lives of Indigenous people living with EOD and their families and caregivers as well [8, 9, 11]; this may offset the health inequities that impact Indigenous people in accessing sufficient resources and support for dementia care for younger Indigenous people [12] in the setting of the general lack of resources for younger people living with dementia [13]. An additional layer of complexity relates to the lived experiences of Indigenous people living with EOD in urban settings. The populations of Indigenous (FN, Metis and Inuit) peoples residing in urban areas (defined as “places that have a population of at least 1,000 and no fewer than 400 persons” [14]) is increasing, with the last Canadian census reporting that this is where 60% of the total Indigenous population resides [15]. Data regarding Indigenous people’s experiences and perspectives living in urban areas are underrepresented and often outdated [14, 16, 17] and available annual health information collected is primarily quantitative on-reserve FN data and includes little qualitative data [18].

In response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada’s Calls to Action (2015) and specifically Health Related Calls to Action to improve the health of Indigenous people, the aim of this study was to develop in-depth understanding of how EOD is conceptualized and experienced by urban Indigenous populations.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This was a small-scale qualitative phenomenological study [19]. A phenomenological analysis aimed to explore and share in detail how individuals make sense of their experiences [19]. Given the history of mistreatment of Indigenous people stemming from the historical trauma of colonization, and the use of exploitative and culturally inappropriate research methodologies [20], phenomenology is an appropriate methodology as it honors methods of oral storytelling and narratives used in Indigenous traditions and cultures [21]. Throughout the completion of this work, an ethical and thoughtful approach was used to ensure that we build on the principles of ownership, control, access and possession (OCAP®) [22] in an urban context. The study was approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (REB19-1386).

Recruitment

We recruited three types of participants to the study between December 2019 and February 2020. This included: 1) persons residing in the urban center of Calgary, Alberta (population 1.33 million) and the surrounding metropolitan areas, self-identifying as Indigenous (FN, Metis or Inuit), with an EOD diagnosis; 2) persons who were friends or family members of a self-identified Indigenous person with an EOD diagnosis; and 3) health service providers specifically involved in providing care for Indigenous people with an EOD diagnosis living in Calgary. We used a broad recruitment strategy including posting advertisements at urban Indigenous community services including the Elbow River Healing Lodge (an urban Indigenous primary healthcare service) and the Metis Nation of Alberta Region III. Despite our broad recruitment strategy, we were unable to recruit any participants with a diagnosis of EOD. Participants were provided with honoraria as a thank you for their participation and recruitment was discontinued in early March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data collection

Data were collected through in-depth, semi-structured interviews by PB and PR. Interview guide questions were based on previous research and experience conducted by the research team with guiding questions to prompt participants to discuss their experiences of EOD and their experiences of EOD health services (Supplementary Material 1, www.neurores.org). The guiding questions were semi-structured to ensure the opportunity was provided for any additional discussion and to explore themes that were brought up or emphasized by the participants themselves. During the process of data collection, it was emphasized that participants had full control over where and when they wanted to meet for the interview and themes were brought back to the participants after analysis. The semi-structured and in-depth quality of the interviews provides participants with control in the research setting.

To enhance the rigor of the study while also undertaking peer-debriefing, the study team met after each interview to discuss the process and interview content before the next interview. Each semi-structured interview was transcribed verbatim by the same member of the team (PB); any identifying characteristics such as names of individuals and communities were not included in the transcript to protect anonymity. Audio recording was reconciled to the transcripts as an additional step to ensure immersion in the data prior to analysis.

Data analysis

A thematic qualitative analysis was conducted on the transcribed interviews using Qualitative Description [23] using NVivo12 software [24]. A multi-step coding process was conducted by the study team (PB and PR). The transcripts were thoroughly read through multiple times and descriptive codes were identified. The codes where then organized into larger analytical categories and those subheadings were thematically synthesized to construct sub-themes and overarching themes. Members of the study team not directly involved in the coding thematically analyzed random selections of interview data (CR). All codes and themes were discussed and revised as a team to achieve agreement with further triangulation on data analysis. Throughout the analytical process ongoing development of themes and sub-themes were discussed with study participants for input and confirmation/disconfirmation one to two times per participant. This was done to enhance rigor through member checking but also to ensure that the analysis accurately represented the experiences of the participants and that the research team did not misinterpret or misrepresent participant experiences.

| Results | ▴Top |

Participants

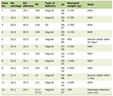

A total of five participants were recruited and interviewed, and participant demographics are presented in Table 1 (with pseudonyms). Five out of the six of the semi-structured interviews were held in-person at a time and location that was most convenient to the participant, and the interview with “Alice” was held over a Skype call. Each interview session was recorded after consent was confirmed and was between 30 and 60 min in duration.

Click to view | Table 1. Participant Demographics |

Themes

Four overarching themes emerged from the thematic analysis: 1) urban Indigenous understanding of living with EOD; 2) Indigenous family experiences of adjusting to EOD; 3) western approaches to healing and thriving with EOD; and 4) Indigenous ways of healing and thriving with EOD. Each of these themes is discussed below.

Theme 1: urban Indigenous understandings of living with EOD

Participants described varying coping mechanisms with symptoms or a diagnosis of EOD. Some individuals described family members being aware of their diagnosis but were too afraid to tell their family, while recognizing the potential need for more family support with daily activities and decision making.

“And you know, I question myself if I ever get a dementia, I would like to know. I don’t know if I have it and I don’t know if I have - and I want to know if I have it… The thing is that I read that dementia can happen in any age now. And for me that’s very interesting to me. Like where does it come from? Where does it start? What are the signs and symptoms?” - Dana

Participants perceived that Indigenous people in urban areas experienced greater disconnection from culture and community that may support them and their family members while living with EOD. Participants also described difficulties in connecting to elders and traditional teachings in urban settings. Trauma from colonization and residential schools was recognized by all participants and it was emphasized that the history of trauma caused by colonization and residential schools may cause fear of seeking treatment or care from medical institutions.

“ .. but I think talking about specifically Indigenous people’s trauma in Canada, you know thinking about colonization and the Indian Act… And I think you know a lot of maybe fear of seeking medical attention - you know that is a lot of common experience that is shared.” - Alice

The differences between traditional and western understandings of dementia were also discussed by all participants. Traditional ways of knowledge were described to be more holistic, circular and interconnected through generations. In some cases, a diagnosis of dementia or any other chronic illness was not necessarily negatively viewed, but part of a plan that the creator had designed. Although differences persisted between western and traditional understandings of dementia, one specific way of knowing was not ascribed to be better than the other but it was clear that it was felt these differences could cause misunderstandings and disconnect the people seeking and providing health services.

“Another approach is to be inclusive and have respect for Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing. So not discredit western medicine - but I think western medicine or western premonitions need to acknowledge that there are ways of knowing, being and doing that Indigenous communities and Indigenous peoples have been living for thousands and thousands of years… And so instead of suppressing it, why don’t we just uplift both and allow the person to decide which way they turn for support. As opposed to enforcing one way and the only way that you are going to get better.” - Alice

Theme 2: Indigenous family experiences of adjusting to EOD

There was considerable impact on family members supporting someone living with EOD. After witnessing a family member experience dementia, participant Dana was concerned with developing EOD and wanted to get tested. Alternatively, Trish had family members living with EOD and did not want to be tested avoided thinking about the potential implication to her own health.

“I’m not going to lie and say that it is not on the back of my mind almost daily. That I wouldn’t end up like my sister in the next 5 or 10 years… But also if that happens. It happens. And I think there are some parts in my life that I don’t mind forgetting and so I don’t approach it as this horrible outcome” - Trish

Family members expressed feelings of sadness when witnessing the decline of memory and cognitive ability in their family members living with dementia. Family members also expressed a sense of guilt and yet relief when a loved one living with dementia passed away.

“dementia can take a toll on the person who is caring for them. Because you are worried. Worrying about falls. Worrying about walking out at night. Worrying about if they took their meds. If they didn’t take their meds. Did they fall in the tub?” - Dana

“And when people do pass, almost a sense of relief… People will not say that. But it is.” - Trish

Theme 3: western approaches to healing and thriving with EOD

Participants reported that there would always be a need for Indigenous people who live in non-urban areas to access urban center for healthcare, in addition to those that live in urban areas, and expressed difficulties with transitioning from a non-urban to urban contexts with different support systems available. Issues with travelling far distances and transportation cost were mentioned, as well as issues deciding on which family members or friends should accompany them to urban areas.

“When you are in an urban centre the services are going to be all over the place so finding your way to get to those services can be difficult.” - Trish

Healthcare professionals reported difficulty connecting younger Indigenous patients living with EOD to specialist services as the majority of dementia services in Calgary are catered towards older people living with dementia. Participants expressed a lack of Indigenous specific healthcare services available in urban centers that are culturally appropriate and the already limited culturally appropriate healthcare services that were available were not specific to EOD. This lack of services was identified as an issue for on-reserve health access in addition to urban settings:

“I do think on reserve especially there are diagnosis problems, access to primary care issues perhaps a delay in diagnosis, perhaps a harder to manage the condition with effective interventions, lack of skill set like rehab or whatever, lack of facilities, Lack of long term care or hospital wards that may be required. A lot of these barriers that are well known for FN living on reserve.” - David

“So like just recognizing that what our entire population here is vulnerable and when you like when you have early-onset cognitive issues on top of that, like the ability to navigate the system is severely compromised and you need people to help them to kind of work on getting proper housing and to make sure that their health services that are safe and stuff. It is quite challenging” - James

Other issues accessing western health services in urban settings included experiences of racism and stereotyping towards Indigenous people, especially when visibly Indigenous. For Indigenous peoples living with EOD these negative experiences can be especially difficult and can lead to increased fear of seeking healthcare services. Participants mentioned they are aware that stereotyping, bias, and racism against them exist within the urban centers and resulted in patients feeling unwelcome. Feelings of isolation were amplified with experiences of racism in urban areas.

“So again, coming back to that institutional and systemic racism. I think that is a very real experience for many Indigenous people coming from their communities to urban centres to seek medical attention. The barrier of isolation - of sort of being misunderstood.” - Alice

“There are a whole host of problems; homelessness, addiction that are never getting a specific diagnosis because of complex reasons and are sort of struggling.” - David

Theme 4: Indigenous ways of healing and thriving with EOD

There was an expressed need from participants for urban healthcare services to implement Indigenous knowledge of healing including the inclusion of elders and holistic services. Incorporating traditional knowledge keepers into healthcare services in a culturally appropriate manner and emphasizing that healthcare services must find a way to promote multiple ways of knowing priorities for the participants. Suggestions included creating spaces in healthcare centers for smudging or sweat lodges, creating culturally safe EOD diagnostic tools by collaborating with Indigenous communities, as well as having centralized healthcare services and systems that are Indigenous-specific and Indigenous-led.

“Like having a safe space, I think, for victims of residential schools or runways or that are Indigenous people to have - like a safe space for them to be able to talk.” - Dana

Health professionals identified the need to further educate healthcare staff about the histories and cultures of the Indigenous peoples who engage with the health system. Culturally safe healthcare services and training for healthcare providers in the local area were getting better but they could be expanded and further improved.

“I would say that on reserve, many more of my patients are kind of more engage in a traditional wellness kind of sort of thing. Like so you know yeah, we would be meeting with people to do smudges and things like that. What’s the word I want to say? It’s more natural there. It is just part of what is happening there.” - James

All participants identified the need for extra support for family members involved in the care of the individual with EOD, including the availability of counselling services such as support groups or sharing/healing circles. Because many individuals living with dementia prefer to stay in their home rather than transition to a care facility, there is an increased need for home care supports. Collaborating with Indigenous peoples as an important aspect of designing and implementing Indigenous EOD services such as diagnostic tools and interventions that are culturally appropriate in urban contexts was discussed by all the participants. This approach targets the heterogeneity of the Indigenous peoples and their needs and the needs for their specific community. Participants also expressed the need for more research in terms of EOD in Indigenous populations. This included assessing the current state of services, understanding the underlying causes and scope of EOD in Indigenous populations.

“So like just recognizing that what our entire population here is vulnerable and when you like when you have early-onset cognitive issues on top of that, like the ability to navigate the system is severely compromised and you need people to help them to kind of work on getting proper housing and to make sure that their health services that are safe and stuff.” - James

This study works to address the TRC’s Health Related Calls to Action numbers 20-22 [25]. The TRC’s Call to Action number 20 requires that the health needs of Indigenous people residing off-reserve must be recognized and addressed [25], and this study provides some insight into the experiences of healthcare providers and family members of Indigenous people living with EOD in an urban center of Calgary, Alberta. TRC’s Call to Action number 21 requires that there is sustainable support for new and existing Indigenous healing centers [25]. Our results indicate a need to support new and existing Indigenous healing centers including services that specialize in EOD for Indigenous people. The health professionals that took part in this study are familiar with the locally available traditional healing options and still recognized the need for improved access to non-western healthcare. The TRC’s Call to Action number 22 requires that the Canadian healthcare system recognize the importance of traditional Indigenous healing practices and work collaboratively with Indigenous people to integrate these practices as treatment where requested [25]. This aligns with study participants’ concerns that western, urban healthcare services currently do not incorporate traditional knowledge and healing methods into health services for EOD.

The National Dementia Strategy for Canada recognizes the diverse needs and experiences of Indigenous communities in relation to dementia, and the importance of supporting Indigenous communities and organizations with dementia in culturally appropriate and culturally safe ways while maintaining a distinctions-based approach to recognize differences among FN, Inuit, and Metis cultures [26]. As reflected in our findings, the strategy also recognizes the importance of engaging Indigenous communities and organizations in understanding unique dementia challenges that they face, conducting and strengthening ongoing surveillance of dementia in Indigenous communities, and facilitating the development of dementia solutions for FN, Metis and Inuit communities of Canada to improve the quality of life for people living with dementia and caregivers in those communities [26]. In terms of diagnoses, standardized cognitive testing has been shown to be less accurate for Indigenous peoples, possibly resulting in misdiagnosis, and the strategy highlights the need to work collaboratively with and engage Indigenous communities to develop culturally safe and culturally appropriate tools for diagnosis that are not currently widely used, but are in development [26]. However, this strategy continues not to be specific to EOD and focuses more on the populations of the Indigenous people that live in non-urban settings, highlighting the need to include more of the experiences of Indigenous peoples with EOD that live in urban settings in national dementia strategies.

The inclusion of urban Indigenous experiences is important for multiple reasons. Although urban center may offer more healthcare services, Indigenous people are often met with barriers that hinder their access to such services. Research shows that Indigenous peoples face challenges like lack of financial support, social exclusion, discriminatory practices, as well as interpersonal and systemic racism that create barriers to healthcare access [27]. Indigenous people living in urban areas report experiencing higher rates of racism and discriminatory practices when accessing healthcare services [28] and report that healthcare workers show a lack of understanding of historical state violence and how trauma is related to health outcomes [29]. Discriminatory practices reduce people’s trust of healthcare providers, trigger a lack safety for clients in care facilities, and discourage clients and healthcare providers from speaking out against discrimination that occurs [30]. Moreover, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples outlines that Indigenous peoples should have full access to healthcare services in ways that reflect and are responsive to Indigenous worldviews and conceptions of health, without discrimination [31].

The importance of acknowledging the cultural, socioeconomic, and past experiences of the Indigenous individuals living with EOD that seek treatment in urban centers was also clearly expressed throughout the findings. Guidance for this acknowledgement and inclusion in health services and systems exists in ways applicable to dementia care design. A framework for cultural competency in healthcare practice that touches on the aspect of cultural competency and the physician’s role in healthcare for Indigenous peoples is the CanMEDS-FM 2017, which is a competency framework designed for all family [32], and more recently the Indigenous health supplement [33] that adapts the CanMEDS-FM 2017 document specifically for Indigenous health. These frameworks emphasize the need for a more holistic and culturally appropriate approach to healthcare practices, which was reflected in our findings [32]. The framework introduces the concept of “community-adaptive competence”, where the dynamic role of the physician to adapt their competence to meet the needs of the community they are serving [32]. In the findings, the importance of collaborating with Indigenous healthcare providers, other social workers, and Indigenous communities was emphasized. One of the competencies of the framework is that family physicians should value continuity and collaboration with other healthcare providers and relationality with patient, families, and communities to optimize patient outcomes [32, 33]. Overall, the CanMEDS-FM 2017 framework is a comprehensive example of how healthcare professionals can conceptualize enhanced cultural safety when working with Indigenous people living with EOD, their families and communities.

Limitations

The sample size was small (n = 5), though does provide valuable preliminary evidence for an understanding on themes related to Indigenous experiences living with EOD. It will not capture all perspectives and experiences on being Indigenous and living with EOD in an urban setting. Another limitation of the study was none of the participants had a diagnosis of EOD themselves. Though three participants had experience of loved ones living with EOD, it is always crucial to include the voice of those living with dementia when understanding gaps and unmet needs. These findings may provide preliminary information towards better understanding of Indigenous experiences with EOD, but this needs to be verified using a larger population.

Conclusion

The findings of this project provide a foundation to our understandings of urban Indigenous experiences of EOD as well as dementia more broadly. Through a better understanding of the Indigenous experiences of dementia, urban healthcare providers and other services can be more aware of the challenges that Indigenous people living with dementia may face and more so for those living with EOD. This work provides evidence to inform future, larger-scale research concerning the co-design of health services specifically for EOD. This will become increasingly important as many Indigenous people are living in urban contexts and will be accessing healthcare with western health care systems and professionals providing care.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Semi-structured interview guide.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained for all participants prior to any study related activities.

Author Contributions

LC, RH, EB, PR and CB were involved in project design and methodological planning. Data were collected through in-depth, semi-structured interviews by PB and PR. Data analysis was completed by PR, PB, CR and MO and overseen by PR and CB. Organization and editing were done by MO and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

EOD: early-onset dementia; FN: First Nations; OCAP®: Ownership, Control, Access and Possession; TRC: Truth and Reconciliation Commission

| References | ▴Top |

- Rossor MN, Fox NC, Mummery CJ, Schott JM, Warren JD. The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(8):793-806.

doi - Parker RM. Dementia in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Med J Aust. 2014;200(8):435-436.

doi pubmed - Maslow K. Early onset dementia: A national challenge and future crisis [Internet]. Alzheimer's Association. 2006 [cited October 27, 2021]. Available from: https://www.alz.org/national/documents/report_earlyonset_full.pdf.

- Maslow K. Early onset dementia: A national challenge and future crisis summary. [Internet]. 2013 [cited October 27, 2021]. Available from: https://www.alz.org/national/documents/report_earlyonset_summary.pdf.

- Zhu XC, Tan L, Wang HF, Jiang T, Cao L, Wang C, Wang J, et al. Rate of early onset Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3(3):38.

- Jacklin KM, Walker JD, Shawande M. The emergence of dementia as a health concern among First Nations populations in Alberta, Canada. Can J Public Health. 2012;104(1):e39-44.

doi - Li SQ, Guthridge SL, Eswara Aratchige P, Lowe MP, Wang Z, Zhao Y, Krause V. Dementia prevalence and incidence among the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations of the Northern Territory. Med J Aust. 2014;200(8):465-469.

doi pubmed - Stevenson S. Wellness in early onset familial Alzheimer disease: experiences of the Tahltan First Nation [Internet]. Vancouver: National Core for Neuroethics. 2014 [cited October 27, 2021]. Available from: https://med-fom-neuroethics.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2015/08/GTP-Wellness-in-EOFAD-s.pdf.

- Cabrera LY, Beattie BL, Dwosh E, Illes J. Converging approaches to understanding early onset familial Alzheimer disease: A First Nation study. SAGE Open Med. 2015;3:2050312115621766.

doi pubmed - Hayter C, Vale C, Alt M. HACC service models for people with younger onset dementia & people with dementia and behaviours of concern: issues for aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds [Internet]. Armidale: department of ageing, disability & home care & ageing, disability & home care (N.S.W.).; 2008 [cited October 27, 2021]. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20140309093209/https://www.adhc.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/file/0006/228147/29_CALD_ATSI_Dementia_Research_Feb08.pdf.

- Butler R, Dwosh E, Beattie BL, Guimond C, Lombera S, Brief E, Illes J, et al. Genetic counseling for early-onset familial Alzheimer disease in large Aboriginal kindred from a remote community in British Columbia: unique challenges and possible solutions. J Genet Couns. 2011;20(2):136-142.

doi pubmed - Goldberg LR, Cox T, Hoang H, Baldock D. Addressing dementia with Indigenous peoples: a contributing initiative from the Circular Head Aboriginal community. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2018;42(5):424-426.

doi pubmed - Hutchinson K, Roberts C, Roach P, Kurrle S. Co-creation of a family-focused service model living with younger onset dementia. Dementia (London). 2020;19(4):1029-1050.

doi pubmed - Place J. The health of Aboriginal people residing in urban - NCCIH [Internet]. The health of aboriginal people residing in urban areas. 2013 [cited October 27, 2021]. Available from: https://www.nccih.ca/docs/emerging/RPT-HealthUrbanAboriginal-Place-EN.pdf.

- Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census - Canada [Internet]. www12.statcan.gc.ca. 2016 [cited October 27, 2021]. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-can-eng.cfm?Lang=Eng&GK=CAN&GC=01&TOPIC=9.

- Young TK. Review of research on aboriginal populations in Canada: relevance to their health needs. BMJ. 2003;327(7412):419-422.

doi pubmed - Wilson K, Young TK. An overview of Aboriginal health research in the social sciences: current trends and future directions. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67(2-3):179-189.

doi pubmed - Waldram J, Herring DA, Young TK. Aboriginal health in Canada: historical, cultural, and epidemiological perspectives. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 2006.

- Smith JA. Qualitative psychology a practical guide to research methods. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2015.

- Weaver HN. The challenges of research in Native American communities. Journal of Social Service Research. 1997;23(2):1-15.

doi - Struthers R, Peden-McAlpine C. Phenomenological research among Canadian and United States Indigenous populations: oral tradition and quintessence of time. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1264-1276.

doi pubmed - The First Nations principles of OCAP® [Internet]. The First Nations Information Governance Centre. 2021 [cited October 27, 2021]. Available from: https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/.

- Bradshaw C, Atkinson S, Doody O. Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2017;4:2333393617742282.

doi pubmed - QSR international. Learn more about data analysis software [Internet]. [updated 2021; cited October 27, 2021]. Available from: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

- TRC calls to action - indian residential school survivor [Internet]. Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: calls to action. 2015 [cited October 27, 2021]. Available from: https://www.irsss.ca/downloads/trc-calls-to-action.pdf.

- PHA of the Government of Canada [Internet]. Canada.ca. / Gouvernement du Canada; 2019 [cited October 27, 2021]. Available from: http://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/mapping-connections-understanding-neurological-conditions.html.

- Adelson N. The embodiment of inequity: health disparities in aboriginal Canada. Can J Public Health. 2005;96(Suppl 2):S45-61.

doi - Browne AJ. Moving beyond description: Closing the health equity gap by redressing racism impacting Indigenous populations. Soc Sci Med. 2017;184:23-26.

doi pubmed - McLane P, Bill L, Barnabe C. First Nations members' emergency department experiences in Alberta: a qualitative study. CJEM. 2021;23(1):63-74.

doi pubmed - Turpel-Lanford ME. In plain sight: addressing Indigenous-specific racism and discrimination in B.C. health care. [cited October 27, 2021]. 2020. Available from: https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/613/2020/11/In-Plain-Sight-Full-Report.pdf.

- The United Nations General Assembly. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. [cited October 27, 2021]. 2007; Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/Indigenouspeoples/wpcontent/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf. Mississauga, ON: the college of family physicians of Canada; 2017.

- Shaw E, Oandasan I, Fowler N. CanMEDS-FM 2017: A competency framework for family physicians across the Continuum [Internet]. College of Family Physicians of Canada. [cited October 27, 2021]. Available from: https://communities.cfpc.ca/committees∼5/hpen/types/guides/guides/canmeds_fm_2017_a_competency_framework_for_family_physicians_across_the_continuum.

- Kitty D, Funnell S. CanMEDS-FM Indigenous Health Supplement. Mississauga, ON: The College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2020.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.