| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.neurores.org |

Case Report

Volume 3, Number 1, February 2013, pages 42-45

Alternating Progression of Pontine Infarction: A Case Report

Takehisa Hirayamaa, Ken Ikedaa, b, Kiyokazu Kawabea, Yasuo Iwasakia

aDepartment of Neurology, Toho University Omori Medical Center, 6-11-1, Omorinishi, Otaku, Tokyo, 143-8541, Japan

bCorresponding author: Ken Ikeda, Department of Neurology, Toho University Omori Hospital, 6-11-1, Omorinishi, Otaku, Tokyo, 143-8541, Japan

Manuscript accepted for publication February 18, 2013

Short title: Alternating Progression of Pontine Infarction

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jnr181w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

We report a patient with rapid progression of crossed pontine infarction. A 59-year-old man noticed occipital headache and dizziness suddenly. Neurological examination showed medial longitudinal fasciculus syndrome on the left side. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed acute isolated lesion in the left lower midbrain tegmentum. Four hours later, he developed coma, ataxic respiration and quadriparesis with left peripheral facial nerve palsy. MRI disclosed extensive midbrain lesion and alternating lesions in the left upper and the right middle pons. T1-hyperintense lesions existed at the periphery of the basilar artery (BA). Brain magnetic resonance angiography disclosed tapered occlusion at the mid-pontine level of the BA. Arterial walls were irregular in the left vertebral artery and BA. Alternating branch atheromatous occlusion due to BA dissection could contribute to the pathogenesis of crossed pontine infarction.

Keywords: Crossed pontine infarction; Basilar artery dissection; Branch atheromatous occlusion; Paramedian penetrating artery

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Topography of pontine infarction was classified by four vascular territories: anteromedial arterial or paramedian arterial territory; anterolateral arterial territory; lateral arterial territory; and posterior arterial territory [1-4]. Neurological symptoms were characterized by three types of ventromedial, ventrolateral and tegmental pontine syndromes [2-4]. Previous clinicoradiological studies suggested the most common pontine lesion in the paramedian arterial territory [2-4]. Bilateral pontine infarction was reported infrequently [4-7]. Lhermitte and Trelles first described bilateral pontine infarction in 1934 [5]. The frequency of bilateral pontine lesions was 9% in 150 patients with isolated pontine infarction [4]. Otherwise, crossed pontine infarction was defined as alternating lesions at the different levels of the basis pontis. This lesion topography was extremely rare [7]. Here we report clinicoradiological features in a distinct patient with rapid progression of alternating pontine infarction.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

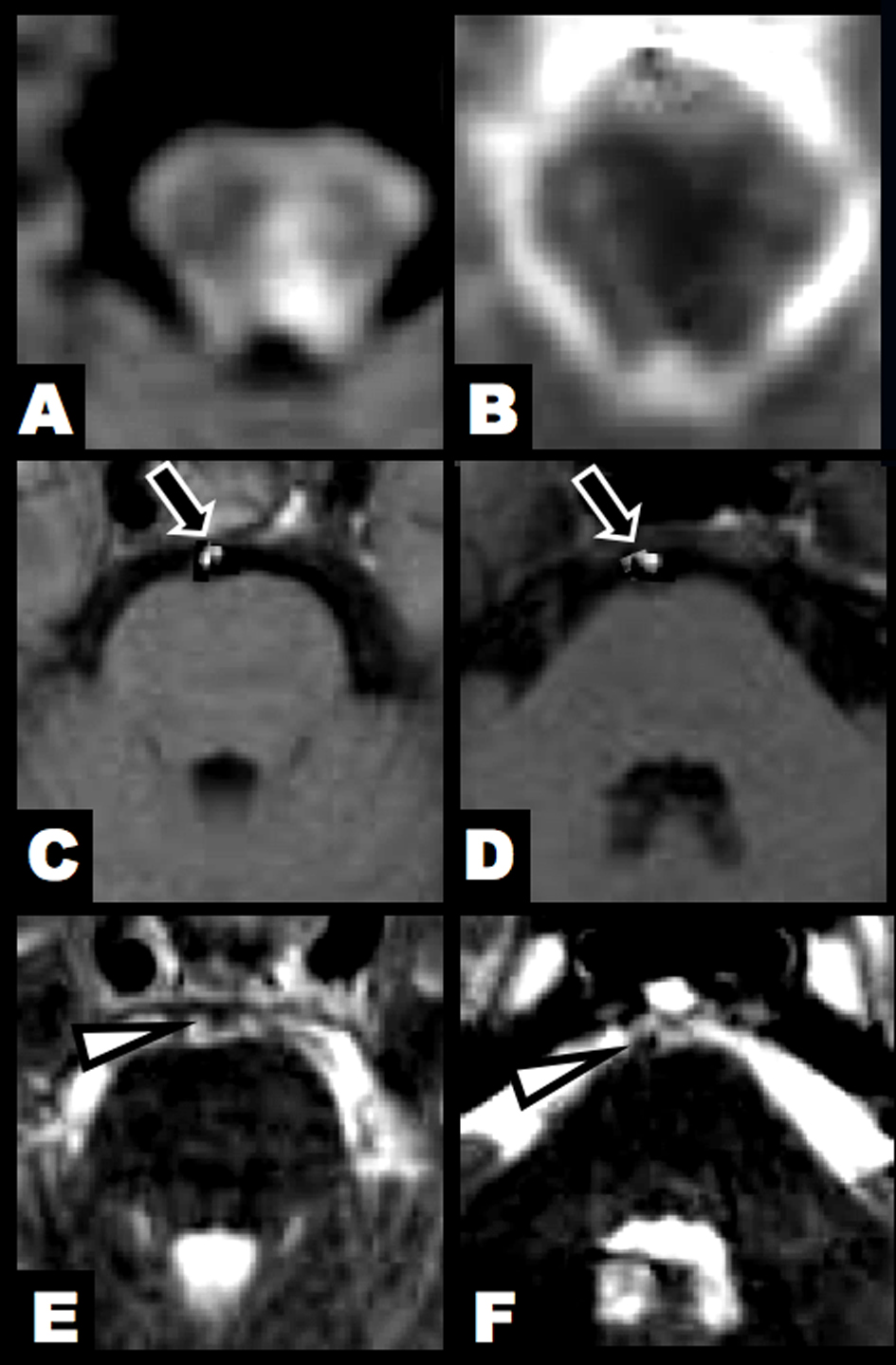

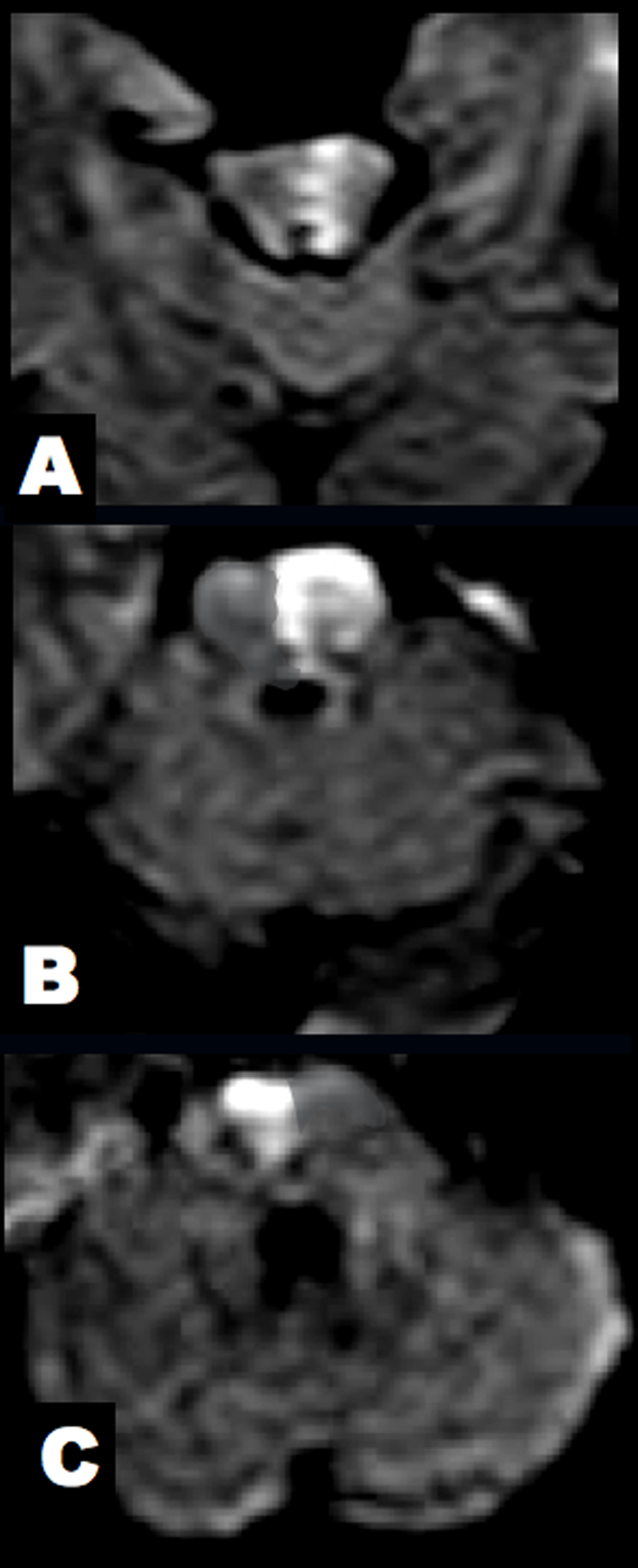

A 59-year-old healthy man had sudden onset of occipital headache and dizziness in the morning. Nausea and speech disturbance were also present. Two hours later, he was admitted to our department. There was no prior history of neck and head trauma. Physical examination was normal except for blood pressure of 134/92 mmHg. Neurological examination showed medial longitudinal fasciculus syndrome on the left side. Muscle stretch reflexes were normal. Babinski’s sign was negative. There were no motor and sensory deficits. Cerebellar ataxia was present in the left extremities. His gait was unsteady. Routine laboratory studies were not remarkable, including electrocardiogram and ultrasound of the carotid artery and heart. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed at 3 hours after clinical onset. Brain diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map revealed an acute lesion at the lower level of the left midbrain tegmentum (Fig. 1A, B). There were no abnormal signal intensities in the pons. T1-hyperintense lesions were found at the upper and middle pontine levels of the basilar artery (BA) (Fig. 1C, D). Brain magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) disclosed tapered occlusion of the BA at the middle level of the pons. Vascular diameters were irregular in the left vertebral artery (VA) and the lower BA. The intracranial right VA was absent (Fig. 2). These radiological findings indicated the diagnosis of acute midbrain infarction due to BA dissection. Ozagrel sodium (80 mg/day, iv) was administered. Four hours later, he developed snore, coma and ataxic respiration. Neurological examination showed the left peripheral facial nerve palsy and right-predominant quadriparesis. Muscle stretch reflexes were increased in the four extremities. Babinski’s sign was positive on both sides. He had no response to pain stimulation in the right face, arm, body and leg. At 7 hours after clinical onset, 2nd DWI disclosed the extensive lesion in the midbrain and new lesions in the right lower and the left upper basis pontis (Fig. 3). Brain MRA was not changed markedly. His family refused conventional cerebral angiography. Clinicoradiological findings speculated BA dissection-associated alternating branch atheromatous occlusion, leading to distinct topography of lower midbrain and crossed pontine infarction. Intravenous administration of heparin sulfate (10,000 units/day, 7 days) and subsequently oral administration of clopidogrel sulfate (75 mg/day) was performed. Two weeks later, his consciousness state was recovered. At 2 months after onset, he was able to talk and sit on the wheelchair, and was transferred to another hospital for rehabilitation.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Brain MRI at 3 hours after clinical onset. (A, B) DWI and ADC map showed an acute lesion in the left lower midbrain tegmentum. (C, D) T1-hyperintense lesions were found in the BA (arrow). (E, F) T2-weighted imaging identified flow void sign of the BA at the upper and middle pontine levels (arrowhead). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Brain MRA showed tapered occlusion of the BA at the middle pontine level. Arterial diameters were irregular in the left VA and BA. The intracranial right VA was absent. (A) Antero-posterior view. (B) Lateral view. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Brain DWI at 7 hours after clinical onset. (A) The midbrain lesion was enlarged. (B, C) New alternating lesions were found in the left upper and right middle pons. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

We described the clinicoradiological changes in a patient with rapid progression of brainstem infarction. DWI lesions spread from the left lower midbrain to the left upper and right middle pons during 3 - 7 hours after clinical onset. Brain MRI and MRA disclosed intramural hematoma, irregular vascular diameters and tapered occlusion in the BA. These arterial findings supported BA dissection.

Fisher first reported lacunar syndrome due to pontine infarction, and the autopsy study elucidated small-artery disease or BA branch disease in those patients [6, 8]. Paramedian pontine infarction was induced by branch atheromatous occlusion. Atherosclerotic plaques might protrude into the lumen of the perforating artery. On the other hand, lacunae or small deep pontine infarction did not involve the medial portion of the basal pons. This infarction type was associated with small vessel lipohyalinosis [6-9]. A previous clinical and MRI study exhibited the etiology in 150 patients with pontine infarction. The most common cause was BA branch disease (39%), followed by small-artery disease (21%), large-artery disease of the vertebrobasilar artery (18%), cardioembolism (8 %) and unknown cause (11 %) [4]. BA branch atheromatous disease or BA occlusion seemed to trigger large infarction in the basal pons, leading to quadriparesis, coma, fluctuating course and local recurrence [3, 6, 10]. With respect to alternating spreading of pontine lesions, only one case was reported previously. A 61-year-old woman developed sudden onset of neck pain and loss of consciousness. Afterwards, coma and quadriparesis occurred. The neurological progression was similar between previous case and our patient. T2-weighted imaging showed alternating hyperintense pontine lesions and an intimal flap in the BA. MRA showed spiral dilatation and tapered occlusion in the BA. These radiological changes indicated BA dissection-induced crossed pontine infarction [7]. In the present patient, T1-weighted imaging showed an intramural hematoma in the BA wall. An intramural hematoma on T1-weighted imaging and an intimal flap on T2-weighted imaging are known as typical signs of arterial dissection [11-13]. Recent radiological studies using high-field MRI demonstrated branch atheromatous changes in patients with pontine infarction [14, 15]. This MRI technique detected a BA plaque in 61% of patients with paramedian pontine infarction and in 73% of patients with small deep pontine infarction [14]. Therefore, intravascular formation of atherosclerotic plaque was implicated in both types of pontine infarction. The pathogenetic mechanism of crossed pontine infarction was speculated in the present patient as follows: 1) BA dissection; 2) alternating branch atheromatous occlusion; and 3) distinct distribution of the paramedian perforating arteries. These concurrent arterial lesions and regional variation could cause alternative brainstem infarction in the lower midbrain, and the upper and middle pons.

In conclusion, we depicted radiological changes of crossed pontine infarction. Incidental overlapping of BA dissection, branch atheromatous plaques and distinct distribution of the paramedian perforating artery might contribute to crossed topography of brainstem lesions in our patient.

Conflict of Interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

| References | ▴Top |

- Gillilan LA. The correlation of the blood supply to the human brain stem with clinical brain stem lesions. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1964;23(1):78-108.

doi pubmed - Kim JS, Lee JH, Im JH, Lee MC. Syndromes of pontine base infarction. A clinical-radiological correlation study. Stroke. 1995;26(6):950-955.

doi pubmed - Bassetti C, Bogousslavsky J, Barth A, Regli F. Isolated infarcts of the pons. Neurology. 1996;46(1):165-175.

doi pubmed - Kumral E, Bayulkem G, Evyapan D. Clinical spectrum of pontine infarction. Clinical-MRI correlations. J Neurol. 2002;249(12):1659-1670.

doi pubmed - Lhermitte J, Trelles OJ. L'arteriosclerose du tronc basilaire et ses conse quences anatomo-cliniques. J Psychiat Neurol. 1934; 51: 91-107.

- Fisher CM. Bilateral occlusion of basilar artery branches. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1977;40(12):1182-1189.

doi pubmed - Kumazawa R, Takizawa S, Okuma H, Shinohara Y. Crossed pontine infarction caused by vertebro-basilar artery dissection. Intern Med. 2005;44(5):520-521.

doi pubmed - Fisher CM, Caplan LR. Basilar artery branch occlusion: a cause of pontine infarction. Neurology. 1971;21(9):900-905.

doi - Caplan LR. Intracranial branch atheromatous disease: a neglected, understudied, and underused concept. Neurology. 1989;39(9):1246-1250.

doi pubmed - Kubik CS, Adams RD. Occlusion of the basilar artery; a clinical and pathological study. Brain. 1946;69(2):73-121.

doi - Iwama T, Andoh T, Sakai N, Iwata T, Hirata T, Yamada H. Dissecting and fusiform aneurysms of vertebro-basilar systems. MR imaging. Neuroradiology. 1990;32(4):272-279.

doi pubmed - Kitanaka C, Tanaka J, Kuwahara M, Teraoka A. Magnetic resonance imaging study of intracranial vertebrobasilar artery dissections. Stroke. 1994;25(3):571-575.

doi pubmed - Hosoya T, Adachi M, Yamaguchi K, Haku T, Kayama T, Kato T. Clinical and neuroradiological features of intracranial vertebrobasilar artery dissection. Stroke. 1999;30(5):1083-1090.

doi pubmed - Klein IF, Lavallee PC, Mazighi M, Schouman-Claeys E, Labreuche J, Amarenco P. Basilar artery atherosclerotic plaques in paramedian and lacunar pontine infarctions: a high-resolution MRI study. Stroke. 2010;41(7):1405-1409.

doi pubmed - Chung JW, Kim BJ, Sohn CH, Yoon BW, Lee SH. Branch atheromatous plaque: a major cause of lacunar infarction (high-resolution MRI study). Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2012;2(1):36-44.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.