| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.neurores.org |

Original Article

Volume 6, Number 5-6, December 2016, pages 95-101

A Study on Clinico-Biochemical Profile of Neonatal Seizure

Dinesh Dasa, b, Sanjib Kumar Debbarmaa

aDepartment of Pediatrics, AGMC, Kunjaban, Agartala, Tripura, India

bCorresponding Author: Dinesh Das, Department of Pediatrics, Agartala Government Medical College & GBP Hospital, Kunjaban, Agartala 799006, Tripura, India

Manuscript accepted for publication December 02, 2016

Short title: Clinico-Biochemical Profile of Neonatal Seizure

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jnr404w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Seizure is the most frequent sign of neurologic dysfunction in the neonate. Biochemical disturbances occur frequently in neonatal seizures either as an underlying cause or as associated abnormalities. In their presence, it is difficult to control seizures and there is a risk of further brain damage. Early recognition and treatment of biochemical disturbances are essential for optimal management and satisfactory long-term outcome. The aims were to study the biochemical abnormalities in neonatal seizures and to describe the clinical presentation, time of onset and its relation to etiology of neonatal seizures.

Methods: The present study included 115 neonates presenting with seizures admitted to neonatal unit, in a teaching institute, Agartala, Tripura, India during the period of 1.5 years from November 2013 to April 2015. Detailed antenatal, natal and postnatal history was taken and examination of baby was done. Then, relevant investigations including biochemical parameters were done and etiology of neonatal seizures and their associated biochemical abnormalities were diagnosed.

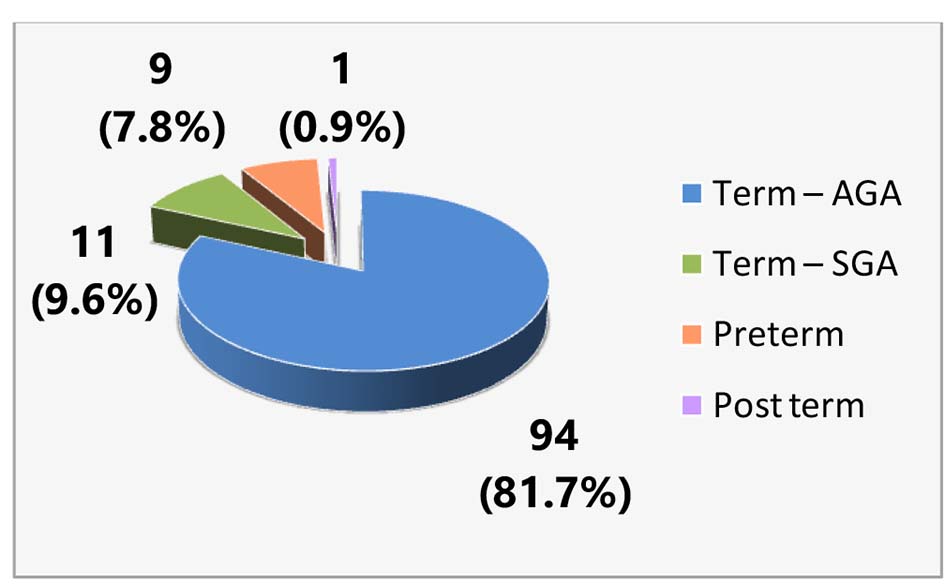

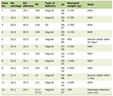

Results: In the present study, out of 115 neonates studied, 105 were full-term, of which 94 (81.7%) were AGA and 11 (9.6%) were SGA, nine (7.8%) were preterm and one (0.9%) was post-term babies. One hundred and thirteen (98.3%) were hospital deliveries and 104 (90.4%) were spontaneous vaginal deliveries. Seventy-five (65.2%) were with birth weight > 2.5 kg. In our study, 82 (80%) cases had onset of seizures within first 3 days. The highest number is seen on first day of life (66, 57.4%). Birth asphyxia was the cause in 92.1% of neonates who developed seizures on first day of life. Subtle seizures were the most common type of seizures in our study (49, 42.6%). Birth asphyxia was the most common cause of neonatal seizures in our study (64, 56%), followed by neonatal meningitis (24, 21%) and metabolic disorders (13, 11%). The most common biochemical abnormality detected in neonatal seizures in our study was hyponatremia (26, 65%), of which 21 (72.4%) were due to hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and the rest were due to neonatal meningitis (5, 55.6%). In metabolic seizures, hypoglycemia (66.7%) was common, and more so in low birth weight babies (55%). Incidence of hypomagnesemia with hypocalcemia occurred in two (1.73%) cases.

Conclusions: The most common etiology of neonatal seizures is HIE and onset is during first 3 days of life. Hyponatremia is the most common biochemical abnormality associated with non-metabolic seizures, mainly HIE. Hypoglycemia is a more common metabolic disorder, more so in low birth weight. Incidence of hypomagnesemia with hypocalcemia is low but recognition of such abnormality has important therapeutic implications.

Keywords: Neonatal seizures; Birth asphyxia; Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy; Hyponatremia; Hypoglycemia; Hypomagnesemia with hypocalcemia

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Neonatal seizures are a common neurological problem in neonates with a frequency of 1.5 - 14/1,000 neonates [1]. A seizure is defined as paroxysmal electrical discharge from brain which may manifest as motor, sensory, behavioral or autonomic dysfunctions [2]. Neonatal seizures are clinically significant as they may be symptomatic of an underlying disorder or primary epileptic condition. The occurrence of seizure may be the first indication of neurological disorder and the time of onset of seizure has relationship with the etiology of seizures and prognosis. Common causes of convulsions in newborn are hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), cerebral infarction and stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, intracranial infections, metabolic disturbances and undetermined [3]. Biochemical disturbances occur frequently in neonatal seizures either as an underlying cause or as associated abnormalities and are often underdiagnosed. Early recognition and treatment of these biochemical disturbances are essential for optimal management and satisfactory long-term outcome. More importance should be given to look for metabolic abnormalities and do biochemical workup in every case of neonatal seizures. This study is designed to determine biochemical abnormalities in relation to clinical presentation which would help with early recognition and treatment and hence better prognosis in neonatal seizures.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This was a prospective observational study conducted at the Neonatal Unit, Department of Pediatrics in a teaching institute in Agartala, Tripura, India. All the neonates from birth to 28 days of life, both inborn and outborn, admitted in the Department of Pediatrics from November 2013 to April 2015 with clinically apparent convulsions, history of convulsions or who developed convulsions during hospitalization were enrolled in the study. Clinical criteria for diagnosing neonatal convulsions were [3]: 1) focal, multifocal, or generalized clonic movement, 2) tonic posturing with or without abnormal gaze, and 3) subtle seizures and spontaneous paroxysmal repetitive motor or autonomic phenomenon like lip smacking, chewing, paddling, swimming, cyclic movements or respiratory abnormalities. Neonates with jitteriness, tetanic spasm and gross congenital malformations, e.g., anencephaly, large occipital meningomyelocele, microcephaly, multiple malformations, dysmorphic features with “syndromic appearance” and mothers not consenting were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was taken from the parent or caregiver prior to enrolment of neonate for the study. Questionnaire-open ended, semistructured pretested, bed head tickets and investigation report were in study tools. Detailed antenatal history, i.e., maternal age, past medical history, parity, gestational age, history of illness during pregnancy, medication during pregnancy, natal history, i.e., evidence of fetal distress, Apgar score, type of delivery, and medication given to mother during delivery were recorded. Baseline characteristics of convulsing neonate including sex, gestational age, weight, head circumference and length were recorded at admission. Clinical details of each seizure episode were recorded, i.e., age at onset of seizures, duration of seizure, number and type of seizure. Seizure was classified into subtle, focal clonic, multifocal clonic, tonic, and myoclonic as per criteria by Volpe [4]. Before instituting specific treatment, blood glucose, total serum calcium levels, Na+, K+, and magnesium were determined. Criteria for diagnosing various biochemical abnormalities [5] were: 1) hypoglycemia: blood sugar < 40 mg/dL (normal range: 40 - 150 mg/dL), 2) hypocalcemia: total serum calcium < 7 mg/dL (normal range: 7 - 10 mg/dL), 3] hypomagnesemia: serum magnesium < 1.5 mg/dL (normal range: 1.5 - 1.8 mg/dL), 4) hypernatremia: serum sodium > 150 mEq/dL (normal range: 130 - 150 mEq/dL), 5) hyponatremia: serum sodium < 130 mEq/dL, 6) hypokalemia: serum potassium < 3.5 mEq/dL (normal range: 3.5 - 5.5 mEq/dL), and 7) hyperkalemia: serum potassium > 5.5 mEq/dL. In addition, complete blood counts, blood culture, USG cranium, MRI/CT, and CSF analysis were done as per the requirement in individual cases. Data were described as mean ± SE and % age. Software used for data analysis was SPSS 15 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences).

| Results | ▴Top |

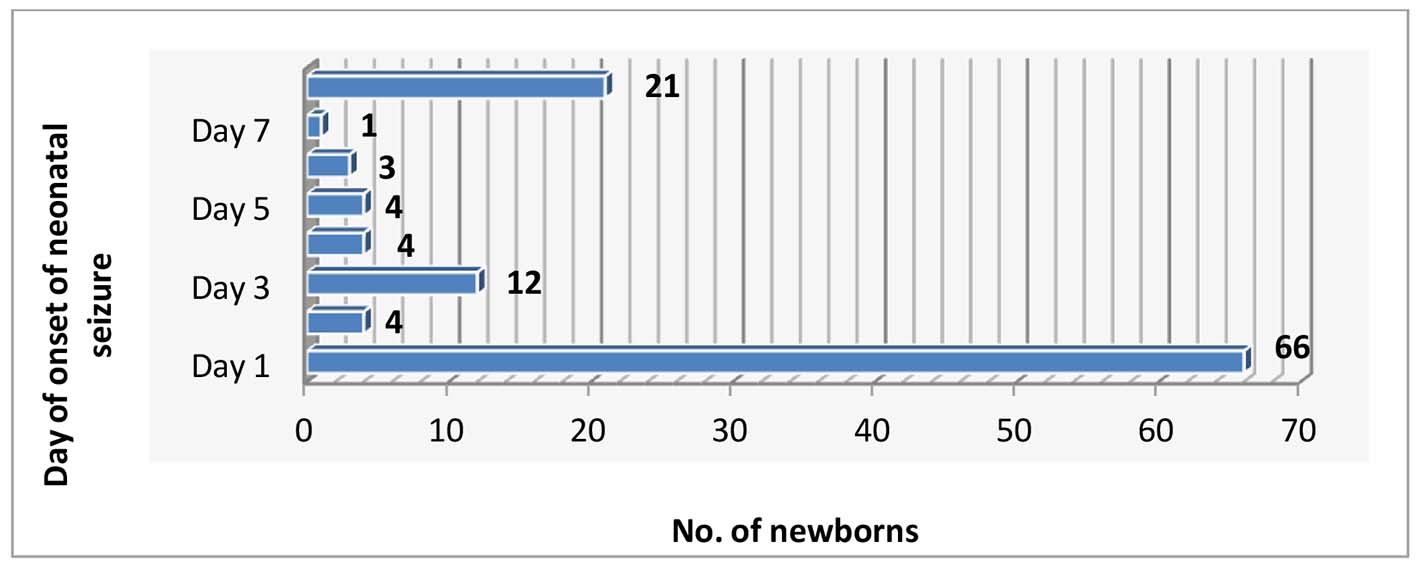

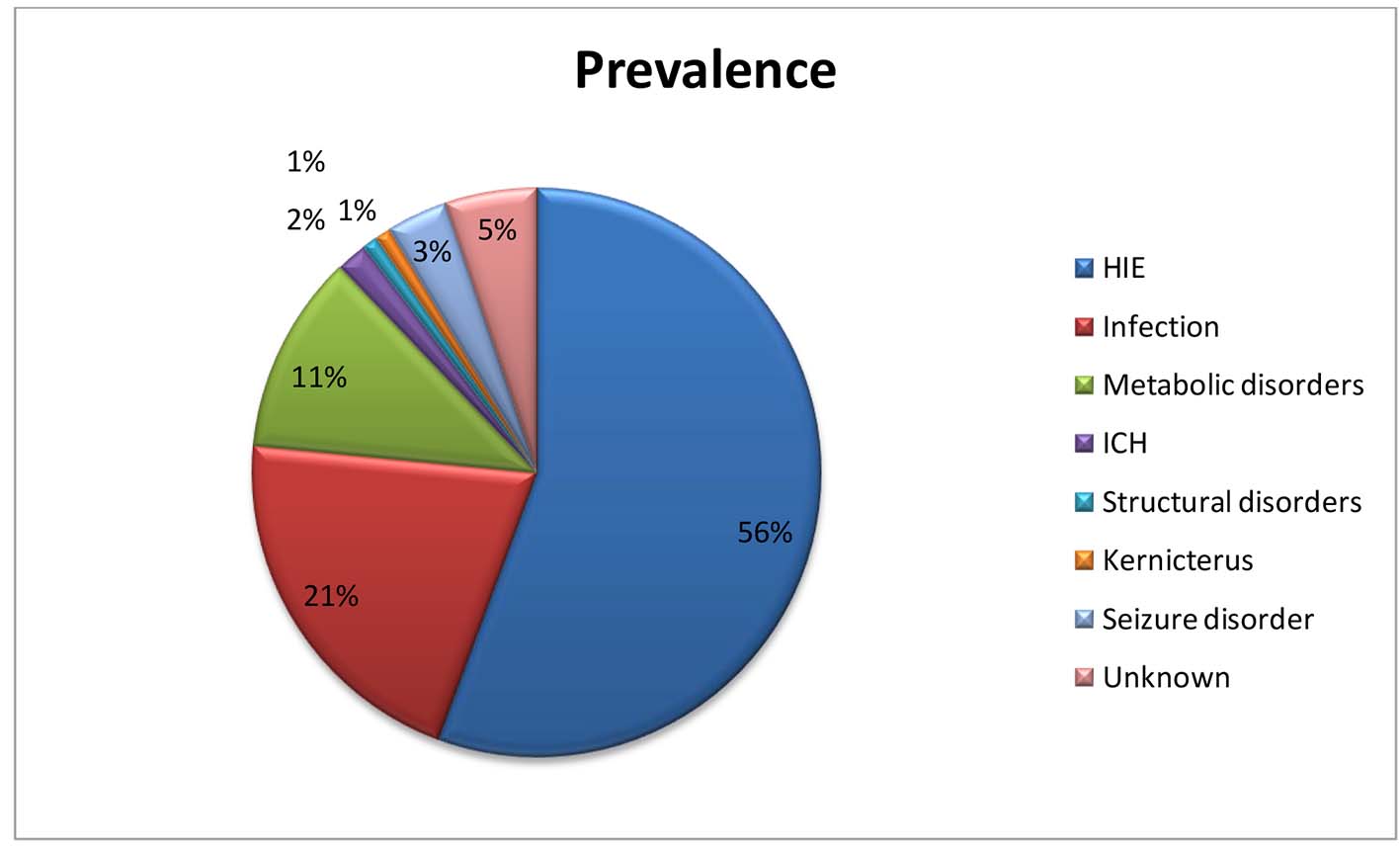

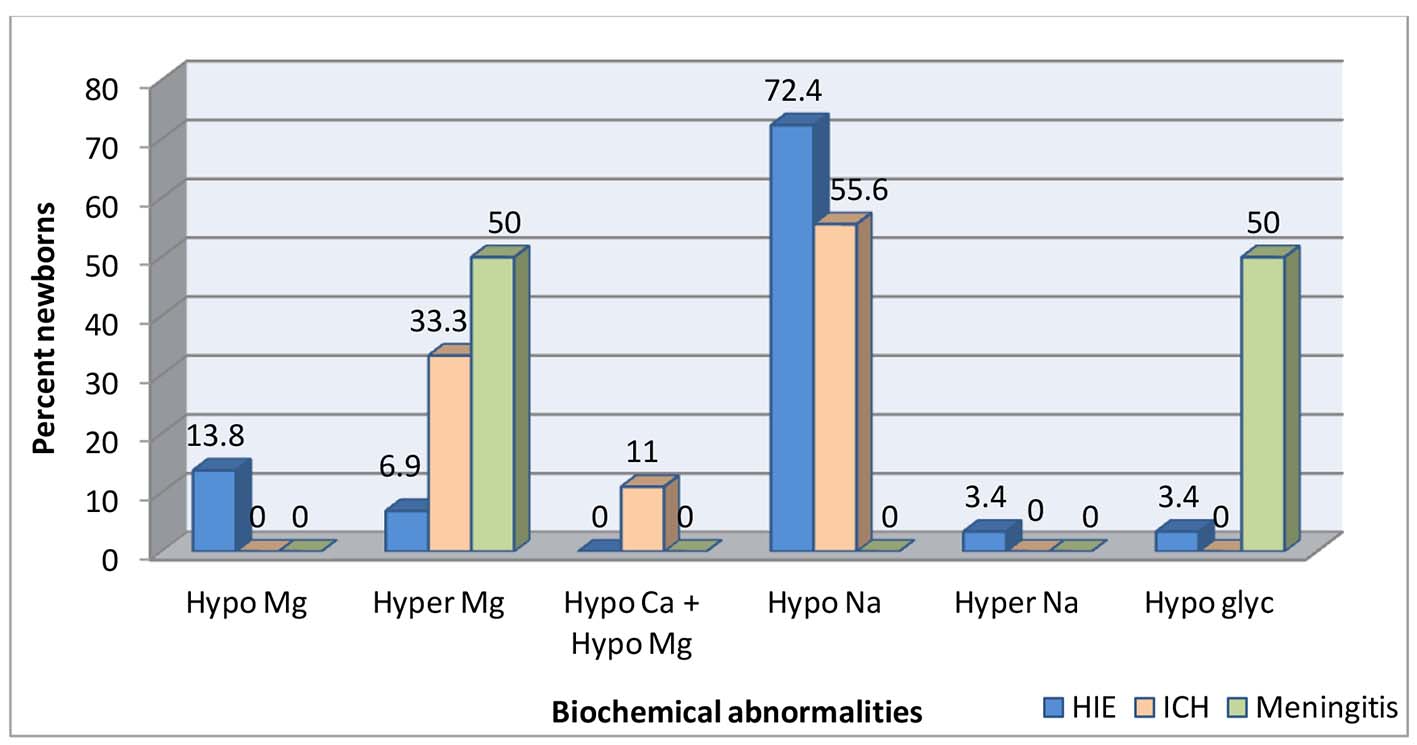

The total number of neonates admitted to Neonatal Unit of Department of Pediatrics, in a teaching institute, Agartala, Tripura, India, during the period of 1.5 years from November 1, 2013 to April 30, 2015 was 1,200. Out of it, 115 neonates had episodes of neonatal seizures. Figure 1 shows out of 115 neonates, preterm babies were nine (7.8%), term babies were 105 (91.3% ) and post-term babies were one (0.9%); 81.7% babies were AGA and 9.6% neonates were SGA in our study. Table 1 shows among the babies 72 (62.6%) were male and 43 (37.4%) were female in our study. Place of delivery of babies with neonatal seizures is shown in Table 1. Two (1.7%) babies were born at home and 113 (98.3%) babies at hospital in our study. Figure 2 shows 104 (90%) babies were born by spontaneous vaginal delivery, nine (8%) babies by cesarean section and two (2%) were by forceps delivery. Table 2 shows in our study 75 (65%) babies were > 2.5 kg, 29 (25%) neonates between 2 and 2.5 kg, and 11 (10%) neonates between 1 and 2 kg. Day of onset of neonatal seizures is shown in Figure 3. In our study, onset of seizure within 24 h of delivery was found in 66 (57.4%) of neonates, while convulsions within 48 h of delivery were seen in four (3.5%) babies. Convulsions in first 3 days of life together were seen in 82 (71.3%) neonates, while from the fourth day of life to seventh day of life, 12 (10.5%) neonates presented with convulsions. Twenty-one (18.2%) neonates developed seizures during 8 - 28 days. Table 3 shows most common type of seizure was subtle type which presented in 49 newborns and constituted 42.6% approximately. Tonic convulsions were present in 39 babies and accounted for 33.9%. The clonic seizure was present in 18 babies and accounted for 15.7%. Subtle with tonic seizures were present in six babies (5.2%) and subtle with clonic seizures in three babies (2.6%). Figure 4 shows most common etiology in our study was birth asphyxia found in 64 cases (56%) of neonatal convulsions. Neonates with meningitis or septicemia constituted 21% cases (second most common). Metabolic derangement as cause of neonatal convulsion was found in 11% in our study which was also comparable to previous studies. Intracranial bleed was etiology for seizures in two cases (2%). Kernicterus and structural disorders were found in one and one newborn, respectively. Seizure disorders were found in 3% of cases and six babies (5%) were included in the undetermined group. Table 4 shows out of 115 neonates, biochemical abnormalities were seen in 53 cases, among which non-metabolic seizures constituted 40 cases and pure metabolic seizures were seen in 13 cases. The most common biochemical abnormality in our study was hyponatremia (26, 65%) seen only in non-metabolic seizures, out of which 21 cases (72%) were due to HIE and five (56%) cases due to neonatal meningitis, while the most common metabolic seizure seen was hypoglycemia (9, 67%). Two (5%) cases of non-metabolic seizures also had hypoglycemia. In preterm, four (80%) had hypoglycemia and one (20%) hypomagnesemia. Table 5 shows in our study in term AGA one (33.3%) had hypermagnesemia, one (33.3%) had combined hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia and one (33.3%) had hypoglycemia. One (20%) term SGA had hypomagnesemia and four (80%) SGA had hypoglycemia. Distribution of patients of non-metabolic seizure in accordance with biochemical profile is shown in Figure 5. HIE was associated with four cases (13.8%) of hypomagnesemia, two (6.9%) cases of hypermagnesemia and one (3.4%) each of hypernatremia and hypoglycemia. Intracranial hemorrhage was associated with one (50%) case of hypermagnesemia and one (50%) with hypoglycemia. Neonatal meningitis was associated with three (33.3%) cases of hypermagnesemia and one (11.1%) with combined hypocalcemia + hypomagnesemia. Levels of magnesium and combined hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia in metabolic and non-metabolic seizures are shown in Table 6. Hypomagnesemia was seen in six (42.9%) cases, out of which four cases were due to HIE and two were due to pure metabolic cause. Seven (42.9%) cases showed hypermagnesemia, of which two (33%) were due to HIE, one (17%) case due to intracranial hemorrhage, three cases due to neonatal meningitis and one case due to pure metabolic cause. Two (14.3%) cases of combined hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia were seen, one due to meningitis and one due to pure metabolic cause.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Distribution of neonatal seizures according to gestational age. |

Click to view | Table 1. Distribution of Gender and Place of Delivery of Babies With Neonatal Seizures |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Type of delivery of babies with neonatal seizures. |

Click to view | Table 2. Birth Weight of Babies With Seizures |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Day of onset of neonatal seizures. |

Click to view | Table 3. Type of Seizures |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Etiology of seizures. |

Click to view | Table 4. Overall Biochemical Profile in Patients With Neonatal Seizures |

Click to view | Table 5. Distribution of Neonate Having Metabolic Seizure in Accordance With Biochemical Profile |

Click for large image | Figure 5. Distribution of patients of non-metabolic seizure in accordance with biochemical profile. |

Click to view | Table 6. Levels of Magnesium and Combined Hypocalcemia and Hypomagnesemia in Metabolic and Non-Metabolic Seizures |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Seizures are most common neurological disorders in newborn period. In our study, out of 115 neonates with seizures, 105 (91.3%) were full-term neonates, of which 94 were appropriate for gestational age (81.7%) and 11 were small for gestational age (9.6%). Nine (7.8%) were preterm and one (0.9%) baby was post-term baby. Majority of neonates with seizure in our study were full-term babies, birth asphyxia was the most common cause of seizures in full-term babies. Similar observations were seen in study by Moayedi and Zakeri where term AGA babies were 83.6%, preterm were 12.7% and post-term were 3.6% [6]. In our study, neonatal seizures were more common in male babies 63%. In our study, 75 (65%) cases were with birth weight > 2.5 kg, 29 (25%) were between 2 and 2.5 kg and 11 (10%) were between 1 and 2 kg. Study by Moayedi and Zakeri also showed similar finding of 73.6% > 2.5 kg and 22.7% < 2.5 kg [6]. In our study, majority of neonates with seizures were born with normal vaginal delivery (90%) followed by LSCS (8%) and outlet forceps delivery (2%). In a study of neonatal seizures by Mahaveer et al, 68.7% were born by normal vaginal delivery, 28.1% by lower segment cesarean section and 3.1% by forceps delivery [7]. In our study, 66 (57.4%) neonates out of 115 neonates with seizures had onset within the first day of life, four (3.5%) on day 2 and 12 (10.4%) on day 3 of life, i.e., 61% within 48 h and 68% within 1 week. Twenty-one (18.2%) neonates had after 8 days of life to 28 days of life. This presentation is consistent with earlier studies [8-10]. We found in our study, subtle seizure in 49 cases (43%) which were most commonly associated with birth asphyxia and preterm babies, followed by clonic seizure in 16% babies with asphyxia or prematurity were the leading causes. Tonic seizures were present in 34% cases and were associated with meningitis and birth asphyxia. Aziz et al [11] reported clonic convulsions are more common while Taksande et al [12] reported subtle seizures as the most common and occurring in 50% cases. In a study of neonatal seizures by Kumar and Gupta, 46.55% were subtle seizures and 21.55% were generalized tonic seizures [9]. In a study of neonatal seizures by Philip et al, subtle seizures were the most common occurring in 51% (27 of 53), followed by focal clonic (42%), multifocal clonic (30%) and GTS (23%) [13]. Birth asphyxia is the most common cause of neonatal seizure in our study (64 of 115 cases, 56%) followed by meningitis in 24 cases (21%). Metabolic seizures were seen in 13 (11%) cases, two cases of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) (2%), one each of structural disorders and kernicterus, and four cases of seizure disorder. Etiology could not be determined in six (5%) cases. In a study on neonatal seizures by Moayedi and Zakeri, etiology of neonatal seizures was HIE (36.4%), followed by infections (19.1%), metabolic disorders (7.3%), ICH (2.7%) and structural disorders (1.8%) [6]. In 32.7% of cases, etiology was not identified. This study had findings similar to our study [6]. Frequency of birth asphyxia as a cause of neonatal convulsions, reported by previous authors like Sood et al [14], Kumar et al [9], and Aziz et al [11], was 45.71%, 48.2% and 44%, respectively and comparable to our data. Neonatal meningitis is one of the important causes of neonatal seizures. In our study, 24 (21%) cases had meningitis. Eight cases were early onset, which presented on or before seventh day. Remaining 16 cases were late onset, which presented after seventh day of life. Parikh et al showed that late onset meningitis is more common than early onset meningitis [15]. Rabindran et al [10] reported meningitis as a cause of neonatal seizures in 7.69% cases whereas Legido et al [16] reported 17.2%, while Aziz et al [11] reported 22% incidence of neonatal infection in neonatal seizures. Our findings are comparable and more likely confounded by hygiene. Intracranial bleed as a cause of neonatal convulsions was found in 2% cases, which is lower than previous reported data like Malik et al [17] reported 9.5% and Aziz et al [11] reported 13% of cases while in our study intracranial bleed accounted for 2% cases which may be because of less premature babies in our study. Rose and Lombroso [18] and Scher [19] reported higher incidence of intracranial bleed in preterm babies. Out of 115 neonates, biochemical abnormalities were seen in 53 cases, among them, non-metabolic seizures constituted 40 cases and pure metabolic seizures were seen in 13 cases. The most common biochemical abnormality in our study was hyponatremia in 26 cases (65%) seen only in non-metabolic seizures, out of which, 21 cases (72%) were due to HIE and five (56%) cases due to neonatal meningitis, while the most common metabolic seizure seen was hypoglycemia in nine (69.2%) cases. Two (5%) cases of non-metabolic seizures also had hypoglycemia. In preterm, four (80%) had hypoglycemia and one (20%) had hypomagnesemia. In term AGA, one (33.3%) had hypermagnesemia, one (33.3%) had combined hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia and one (33.3%) had hypoglycemia. One (20%) term SGA had hypomagnesemia and four (80%) SGA had hypoglycemia. HIE was associated with four cases (13.8%) of hypomagnesemia, two (6.9%) cases of hypermagnesemia and one (3%) each of hypernatremia and hypoglycemia. Intracranial hemorrhage was associated with one (50%) case of hypermagnesemia and one (50%) with hypoglycemia. Neonatal meningitis associated with three (33.3%) cases of hypermagnesemia and one (11.1%) with combined hypocalcemia + hypomagnesemia. Hypomagnesemia was seen in six cases, out of which four cases were due to HIE and two were due to pure metabolic cause. Seven (42.9%) cases showed hypermagnesemia, of which two (33%) were due to HIE, one (17%) case due to intracranial hemorrhage, three cases due to neonatal meningitis and 1one case due to pure metabolic cause. Two (14.3%) cases of combined hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia were seen, one due to meningitis and one due to pure metabolic cause. In a study done on 100 neonates by Estan and Hope, HIE accounted for 37%, intracranial hemorrhage 7%, meningitis 5%, and hypoglycemia 3% [20]. Goldberg in a 10-year review of 81 cases had HIE (16%), ICH (6%), hypoglycemia (6%), hypocalcemia (2%), and meningitis (8%), and remaining were due to congenital abnormalities [21]. Nelson et al in 2006 observed that 10-20% of cases were due to hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia [22].

Conclusion

Neonatal seizures occur more commonly in term babies (91%). Neonatal seizures occur more commonly in male babies. Most of the neonatal seizures occurred in hospital deliveries (98%). Most of them were delivered by spontaneous vaginal delivery (90%). Sixty-five percent of seizures occurred in newborns weighing > 2.5 kg. Most neonatal seizures occur in the first 3 days of life. Highest number is seen on first day of life (57.4%). Birth asphyxia was the cause in 56% in neonates. Seizures due to neonatal meningitis comprise 21%. Subtle seizures are the most common type of seizures (43%) followed by generalised tonic (34%) and metabolic disorder mainly hypoglycemia (8%). The most common biochemical abnormality detected in neonatal seizures in our study was hyponatremia (65%), of which 72% were due to HIE, and rest due to neonatal meningitis (56%). In metabolic seizures, hypoglycemia (67%) was most common more so in low birth weight babies (55%). Neonatal meningitis in our study was the second most common cause of seizures (21%). Early recognition and treatment of biochemical disturbances are essential for optimal management and satisfactory long-term outcome.

| References | ▴Top |

- Airede KI. Neonatal seizures and a 2-year neurological outcome. J Trop Pediatr. 1991;37(6):313-317.

doi pubmed - Mikati MA, Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Stanton BF. Seizures in childhood; Nelson textbook of paediatrics, 19th edition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders[586]. 2011; 2013-2037.

doi - Sankar MJ, Agarwal R, Aggarwal R, Deorari AK, Paul VK. Seizures in the newborn. Indian J Pediatr. 2008;75(2):149-155.

doi pubmed - Volpe JJ. Neonatal Seizures. Neurology of the newborn. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders. 2001; 178-214.

pubmed - Kumar A, Gupta V, Kachhawaha JS, Singla PN. Biochemical abnormalities in neonatal seizures. Indian Pediatr. 1995;32(4):424-428.

pubmed - Moayedi AR, Zakeri S. Neonatal seizure: Etiology and type. J Child Neurology. 2007;2:(issue)23-26.

- Lakhra, et al. Chaturvedi pushpa Clinico - biochemical profile of neonatal seizures in a rural medical college. National neonatology forum. 2003; Hyderabad.

- Plouin P, Kaminska A. Neonatal seizures. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;111:467-476.

- Kumar A, Gupta A, Talukdar B. Clinico-etiological and EEG profile of neonatal seizures. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74(1):33-37.

doi pubmed - Rabindran, Hemant Parakh, Ramesh JK, Prashant Reddy. Phenobarbitone for the Management of Neonatal Seizures - A Single Center Study. Int J Med Res Rev. 2015;3(1):63-71.

- Aziz A, Gattoo I, Aziz M, Rasool G. Clinical and etiological profile of neonatal seizures: a tertiary care hospital based study. Int J Res Med Sci. 2015;3:2198-2203.

doi - Taksande AM, Krishna V, Manish Jain, Mahaveer L. Clinico-biochemical profile of neonatal seizures. Paed Oncall Journal. 2005;2(10).

- Brunquell PJ, Glennon CM, DiMario FJ, Jr., Lerer T, Eisenfeld L. Prediction of outcome based on clinical seizure type in newborn infants. J Pediatr. 2002;140(6):707-712.

doi pubmed - Sood A, Grover N, Sharma R. Biochemical abnormalities in neonatal seizures. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70(3):221-224.

doi pubmed - Parikh Tushar B, Udani Rekha H, Nanavati Ruchi N. C-reactive protein and diagnosis of neonatal meningitis. In: Farnandez A, Dadhich JP, Saluja S, Editors. Abstracts, XXIII Annual Convention of National Neonatology Forum, Dec. 18-21 (issue):2003. Hyderabad. 2003; p. 157-158.

- Legido A, Clancy RR, Berman PH. Neurologic outcome after electroencephalographically proven neonatal seizures. Pediatrics. 1991;88(3):583-596.

pubmed - Malik BA, Butt MA, Shamoon M, Tehseen Z, Fatima A, Hashmat N. Seizures etiology in the newborn period. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15(12):786-790.

pubmed - Rose AL, Lombroso CT. A study of clinical, pathological, and electroencephalographic features in 137 full-term babies with a long-term follow-up. Pediatrics. 1970;45(3):404-425.

pubmed - Scher MS. Controversies regarding neonatal seizure recognition. Epileptic Disord. 2002;4(2):139-158.

pubmed - Estan J, Hope P. Unilateral neonatal cerebral infarction in full term infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1997;76(2):F88-93.

doi pubmed - Goldberg HJ. Neonatal convulsions: a ten year review. Arch Dis Childhood. 1982;57:633-635.

doi - Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18th ed. Saunders; 2007. p. 2471.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.