| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.neurores.org |

Review

Volume 10, Number 4, August 2020, pages 107-112

The Neurologic Manifestations of Coronavirus Disease 2019

Amjad Elmashalaa, c, Saurav Choprab, Aayushi Garga

aDepartment of Neurology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA, USA

bDepartment of Pathology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA, USA

cCorresponding Author: Amjad Elmashala, Department of Neurology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins Dr, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA

Manuscript submitted June 2, 2020, accepted June 15, 2020, published online June 23, 2020

Short title: Neurologic Manifestations of COVID-19

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jnr603

| Abstract | ▴Top |

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an ongoing global pandemic that has so far affected 216 countries and more than 5 million individuals worldwide. The infection is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). While pulmonary manifestations are the most common, neurological features are increasingly being recognized as common manifestations of the COVID-19, especially in the cases of severe infection. These include acute cerebrovascular disease, encephalitis, and Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS). Here, we review the neuropathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 and the central and peripheral nervous system manifestations of COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19; Coronavirus; Neurologic; Stroke; Myelitis; Encephalitis; GBS; Anosmia

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an ongoing global pandemic that has so far affected 216 countries and more than 5 million individuals worldwide [1]. The infection is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is a part of beta-coronaviruses (CoVs) and shares sequence similarity with SARS-CoV, the cause of 2003 SARS pandemic [2].

CoVs are a group of enveloped viruses with a single-stranded, positive sense RNA genome [3]. Under the electron microscope, they display evenly arranged surface protrusions, giving it a crown-shaped appearance [4]. Based on the phylogenetic characteristics, they are divided into four groups: alpha-, beta-, gamma-, and delta-CoV [4]. The envelope of the beta-CoV consists of five structural proteins, known as spike, envelope, membrane, nucleocapsid, and hemagglutinin-esterase [5]. The spike protein appears to be the key structure for infectivity and virulence as it recognizes and binds to the receptors on the host cells [4-6].

Respiratory droplets and contact are the main routes of transmission for COVID-19; however, there is also evidence for transmission through the digestive tract or through aerosols during a prolonged exposure [4].

| Neuropathogenesis | ▴Top |

The SARS-CoV-2, like SARS-CoV, uses the spike protein to interact with the host angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is expressed in various tissues including the airway epithelial cells, and serves as the entry point for the virus [7, 8]. The ACE2 receptors are also expressed in the glial cells and neurons, thus making them a potential target for the infection [2]. In fact, the neuro-invasive property of CoV has been well demonstrated in previous studies. The SARS-CoV particle has been detected in the brain tissue and in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of affected patients [2]. Furthermore, studies on transgenic mice have shown that SARS-CoV-34, when given intranasally, can spread to the brain, possibly via the olfactory nerves [9]. The neuro-invasive potential of SARS-CoV-2 remains yet to be established. However, a lot may be extrapolated from previous studies on CoVs given its similarity in structure and infection pathways [10]. The hypothesized pathways for central nervous system dissemination of the virus include spread from the systemic circulation or across the cribriform plate via the olfactory bulb [2]. The neurological manifestations may be secondary to host immune responses and/or direct viral toxicity [5].

| Neurological Features | ▴Top |

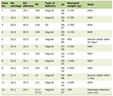

The COVID-19 infection usually manifests as acute pneumonia, similar to that reported in SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-34 infections. The common symptoms of COVID-19 include fever, dry cough, and shortness of breath [11]. A majority of the patients with dyspnea end up needing intensive care [11]. Neurological features are increasingly being recognized as common manifestations of the COVID-19, especially in the cases of severe infection [12]. In this review, we will focus on the reported neurological manifestations of COVID-19 and discuss the current evidence for each of them. A summary of these manifestations is elicited in Table 1 [11, 12-26].

Click to view | Table 1. Neurologic Manifestations of COVID-19 |

Central nervous system manifestations

Cerebrovascular disease

1) Ischemic stroke

A wide range of infections have been associated with increased risk of acute ischemic stroke [27], with respiratory infections posing the greatest risk [28]. A surge of clotting factors and cytokines has been proposed as a potential mechanism for stroke in COVID-19 infection [29, 30].

Acute ischemic stroke has been reported in 2-5% of patients hospitalized due to COVID-19, with a higher incidence reported with severe infections and in patients with advanced age and comorbid conditions, especially hypertension [12, 13].

COVID-19 has impacted acute stroke care by decreasing the number of patients receiving thrombolysis with or without endovascular intervention; however, there has been an increase in the rate of primary thrombectomy due to delayed presentation [31]. This might stem from patients’ and care providers’ concerns about the risk of acquiring infection from the hospital setting. These findings highlight the importance of adopting specific protocols to safely care for stroke patients. The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association released a temporary guidance regarding optimal care of stroke patients during COVID-19 pandemic [32].

2) Hemorrhagic stroke

Hemorrhagic stroke has been reported in patients with COVID-19. Direct neural invasion via ACE2 receptors and dysregulation of blood pressure have been postulated as potential underlying mechanisms for hemorrhagic stroke [10, 33-35]. Future studies are needed to identify the risk factors and outcomes of hemorrhagic stroke in patients with COVID-19.

Encephalitis

Encephalitis refers to inflammation of the brain parenchyma [36]. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy has been reported as a rare complication of respiratory viral infections [37, 38], which might be related to blood brain barrier breakdown and increased cytokine production [39]. The sequences of SARS-CoV genome were detected in the brain tissue of confirmed SARS autopsies [40]. SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 share similar receptor-binding domain genomic sequences [41], which suggests that areas of predilection for infection might be the same.

Moriguchi et al reported the first case of encephalitis associated SARS-CoV-2. Despite a negative nasopharyngeal swab, SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the CSF and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed hyperintensity in the right mesial temporal lobe [14]. A more severe form of encephalitis with hemorrhages was later reported with brain MRI showing hyperintense signals with a ring of contrast enhancement [15].

Seizure

Seizures have been reported to be among the most common neurologic manifestation in patients with severe viral respiratory illnesses [42-45], including CoVs [46]. There has been a single report of focal status epilepticus in a patient with COVID-19 who developed postencephalitic epilepsy [16]. However, one study has evaluated the development of new onset seizures among 304 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and found no increased risk of acute symptomatic seizures [47].

Myelitis

Myelitis, or inflammation of the spinal cord, presents with acute to subacute onset of pyramidal, sensory, and/or autonomic dysfunction according to the spinal cord tracts that are affected [48]. Several respiratory viral infections have been associated with the development of acute post-infectious myelitis [49-52]. The ACE2 receptors, which have been implicated in the pathogenesis of COVID-19, are expressed in the spinal cord [53, 54]. There has been one reported case of acute onset flaccid paralysis of the lower extremities, urinary and bowel incontinence, and a thoracic 10 sensory level in a patient who tested positive for COVID-19 [17]. However, CSF testing and MRI of the spinal cord were not performed so the diagnosis was not confirmed.

Peripheral nervous system spectrum of disorders

Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) and its variants

GBS is a demyelinating disorder characterized by acute to subacute onset of weakness and sensory symptoms ascending over the course of days [55, 56]. A preceding respiratory or gastrointestinal infection is reported in approximately two-thirds of patients [57]. Several mechanisms, based on anecdotal evidence from case reports, have been proposed for the pathophysiology of GBS in COVID-19 patients including para- and post-infectious phenomena. The former has been reported in two cases, where patients developed GBS within 1 week of COVID-19 diagnosis [18, 19]. The post-infectious phenomenon, which involves antibodies’ cross reactivity with neuronal gangliosides, was reported in one case study [58] and a case series of five patients [20]. The clinical course of GBS in COVID-19 has been reported to be similar to that seen with other infections [59].

The GBS variants, Miller Fischer syndrome (MFS) and polyneuritis cranialis, have been reported in two cases of patients with COVID-19. CSF examination was negative for SARS-CoV-2, suggesting a post-, rather than para-, infectious etiology. Both patients had resolution of neurological complaints, except for anosmia and ageusia in the patient with MFS [21].

Anosmia

Anosmia, or olfactory impairment, has emerged as one of the specific clinical features of COVID-19. The exact pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying its development remain unclear. Olfactory disturbance after a viral upper respiratory tract infection is a common cause of transient anosmia and is primarily attributed to conductive olfactory loss secondary to nasal mucosal congestion [60]. However, in a majority of the COVID-19 cases, anosmia is not linked to rhinorrhea or nasal obstruction [22]. Another speculated mechanism involves the direct virus-induced damage to the olfactory neuroepithelium and/or the neuro-invasive potential of SARS-CoV-2, which is supported by the expression of ACE2 and transmembrane serine protease 2 on the olfactory epithelial cells, the receptors involved in SARS-CoV-2 cellular entry [61, 62]. Furthermore, there is evidence for rapid trans-neuronal spread for SARS-CoV after entry through the olfactory bulb in the transgenic mice models [63]; however, this has not been studied specifically in SARS-CoV-2.

There is a high variability in the reported prevalence of anosmia among patients with COVID-19, ranging from 5-47% in the retrospectively conducted studies [23, 12] to 39-86% in the studies based on self-administered questionnaires [22, 24]. There is only one study that evaluated quantitative olfactory function in patients with COVID-19 and found that 98% of patients had some olfactory dysfunction, and 58% had anosmia [25]. All in all, anosmia seems to be a frequent manifestation of COVID-19 and a lower prevalence reported in some studies could in part be attributed to passive instead of active ascertainment and overall underreporting, possibly due to perceived benignity of the symptom.

Olfactory dysfunction has been described to have a sudden onset [64] and can appear as an initial manifestation without any other clinical symptoms in a sizeable proportion of patients with COVID-19 [22]. Short-term follow-up studies have shown that approximately 25-57% of these patients recover their olfactory function, while others may have persistent symptoms even after resolution of the infection [22, 24]. Younger patients and women have been shown to have a higher predisposition to the development of olfactory symptoms [22, 24].

Overall, there seems to be compelling evidence to identify sudden onset olfactory dysfunction as an indicator of COVID-19 infection, even in the absence of other significant symptoms. The American Academy of Otolaryngology has proposed the addition of new onset olfactory dysfunction to the screening symptoms of COVID-19 with prompt infection testing and precautionary isolation in the current epidemiologic context [65].

Ageusia

Along with anosmia, ageusia or gustatory dysfunction has also been confirmed as a significant symptom of COVID-19. Most cases of self-reported ageusia are in general found to be secondary to underlying anosmia [66]. Similarly, in COVID-19, ageusia has been shown to have a significantly positive association with anosmia [22], and is hence thought to be a secondary symptom of underlying anosmia and not a result of damage to the gustatory afferents, per se [25]. Among patients with COVID-19, ageusia has been reported in 45-88% of the cases [22, 24]. Therefore, sudden onset ageusia, usually seen in conjunction with anosmia, has been added to the list of COVID-19 screening symptoms.

Myopathy

Patients with COVID-19 have been reported to have myopathies, with symptoms ranging from myalgias to rhabdomyolysis [12]. Various pathophysiologic mechanisms have been speculated to underly the skeletal muscle injury. Immune-mediated muscle damage has been suggested, given the significant association between occurrence of myopathy and the severity of the inflammatory response [12]. Another possible mechanism is critical illness myopathy or polyneuropathy, which has been described in the SARS-CoV infection, and is associated with prolonged ventilatory assistance, use of neuromuscular blocking agents, and steroids [67, 68]. Finally, the direct viral myotoxicity must also be considered, as described in other viral infections [69-71] and supported by the presence of ACE2 receptors on the skeletal muscle [72]. Myalgia and fatigue have been reported in 44-70% of hospitalized patients [11, 26] and skeletal muscle injury in around 11% of patients [12]. Overall, muscle symptoms appear to be commonly associated with COVID-19 and further studies are needed to elucidate the exact nature of the myopathy.

| Conclusions | ▴Top |

This review summarizes the current clinical evidence for neurologic manifestations of COVID-19. While neurologic features appear to be commonly associated with COVID-19, further studies are needed to explain the exact pathophysiology and clinical course.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in reviewing the literature, drafting the article, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. [cited May 18, 2020]; Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- Baig AM, Khaleeq A, Ali U, Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: tissue distribution, host-virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11(7):995-998.

doi pubmed - Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102433.

doi pubmed - Jin H, Hong C, Chen S, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Mao L, Li Y, et al. Consensus for prevention and management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) for neurologists. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2020.

doi pubmed - Desforges M, Le Coupanec A, Stodola JK, Meessen-Pinard M, Talbot PJ. Human coronaviruses: viral and cellular factors involved in neuroinvasiveness and neuropathogenesis. Virus Res. 2014;194:145-158.

doi pubmed - Perez CA. Looking ahead: The risk of neurologic complications due to COVID-19. Neurol Clin Pract. 2020.

doi - Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, Lely AT, Navis G, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203(2):631-637.

doi pubmed - Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, Graham BS, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367(6483):1260-1263.

doi pubmed - Li K, Wohlford-Lenane C, Perlman S, Zhao J, Jewell AK, Reznikov LR, Gibson-Corley KN, et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus causes multiple organ damage and lethal disease in mice transgenic for human dipeptidyl peptidase 4. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(5):712-722.

doi pubmed - Li YC, Bai WZ, Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):552-555.

doi pubmed - Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506.

doi - Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020.

doi pubmed - Wang M, et al. Acute cerebrovascular disease following COVID-19: a single center, retrospective, observational study. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020.

- Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, Harada D, Sugawara H, Takamino J, Ueno M, et al. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:55-58.

doi pubmed - Poyiadji N, Shahin G, Noujaim D, Stone M, Patel S, Griffith B. COVID-19-associated acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy: CT and MRI features. Radiology. 2020;31(1):5-30.

doi pubmed - Vollono C, Rollo E, Romozzi M, Frisullo G, Servidei S, Borghetti A, Calabresi P. Focal status epilepticus as unique clinical feature of COVID-19: A case report. Seizure. 2020;78:109-112.

doi pubmed - Zhao K, Huang J, Dai D, Feng Y, Liu L, Nie S. Acute myelitis after SARS-CoV-2 infection: a case report. medRxiv. 2020. p. 2020.03.16.20035105.

doi - Zhao H, Shen D, Zhou H, Liu J, Chen S. Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: causality or coincidence? Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(5):383-384.

doi - Virani A, Rabold E, Hanson T, Haag A, Elrufay R, Cheema T, Balaan M, et al. Guillain-Barre Syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. IDCases. 2020;20:e00771.

doi pubmed - Toscano G, Palmerini F, Ravaglia S, Ruiz L, Invernizzi P, Cuzzoni MG, Franciotta D, et al. Guillain-barre syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020.

doi pubmed - Gutierrez-Ortiz C, Mendez A, Rodrigo-Rey S, San Pedro-Murillo E, Bermejo-Guerrero L, Gordo-Manas R, de Aragon-Gomez F, et al. Miller Fisher Syndrome and polyneuritis cranialis in COVID-19. Neurology. 2020.

doi pubmed - Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, Horoi M, Le Bon SD, Rodriguez A, Dequanter D, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020.

- Klopfenstein T, Kadiane-Oussou NJ, Toko L, Royer PY, Lepiller Q, Gendrin V, Zayet S. Features of anosmia in COVID-19. Med Mal Infect. 2020.

doi - Beltran-Corbellini A, Chico-Garcia JL, Martinez-Poles J, Rodriguez-Jorge F, Alonso-Canovas A. Reply to letter: Acute-onset smell and taste disorders in the context of Covid-19: a pilot multicenter PCR-based case-control study. Eur J Neurol. 2020.

doi pubmed - Moein ST, Hashemian SMR, Mansourafshar B, Khorram-Tousi A, Tabarsi P, Doty RL. Smell dysfunction: a biomarker for COVID-19. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020.

doi pubmed - Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020.

doi pubmed - Sebastian S, Stein LK, Dhamoon MS. Infection as a Stroke Trigger. Stroke. 2019;50(8):2216-2218.

doi pubmed - Smeeth L, Thomas SL, Hall AJ, Hubbard R, Farrington P, Vallance P. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(25):2611-2618.

doi pubmed - Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, Hlh Across Speciality Collaboration UK. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033-1034.

doi - Chen C, Zhang XR, Ju ZY, He WF. [Advances in the research of cytokine storm mechanism induced by Corona Virus Disease 2019 and the corresponding immunotherapies]. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi. 2020;36(0):E005.

- Baracchini C, Pieroni A, Viaro F, Cianci V, Cattelan AM, Tiberio I, Munari M, et al. Acute stroke management pathway during Coronavirus-19 pandemic. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(5):1003-1005.

doi pubmed - Aha Asa Stroke Council Leadership. Temporary emergency guidance to US Stroke Centers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: on behalf of the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council Leadership. Stroke. 2020;51(6):1910-1912.

doi pubmed - Steardo L, Steardo L, Jr., Zorec R, Verkhratsky A. Neuroinfection may contribute to pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of COVID-19. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2020;229(3):e13473.

doi pubmed - Xia H, Lazartigues E. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: central regulator for cardiovascular function. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12(3):170-175.

doi pubmed - Sharifi-Razavi A, Karimi N, Rouhani N. COVID-19 and intracerebral haemorrhage: causative or coincidental? New Microbes New Infect. 2020;35:100669.

doi pubmed - Venkatesan A, Geocadin RG. Diagnosis and management of acute encephalitis: A practical approach. Neurol Clin Pract. 2014;4(3):206-215.

doi pubmed - Abdelrahman HS, Safwat AM, Alsagheir MM. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy in an adult as a complication of H1N1 infection. BJR Case Rep. 2019;5(4):20190028.

doi pubmed - Lee YJ, Hwang SK, Kwon S. Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy in Children: a Long Way to Go. J Korean Med Sci. 2019;34(19):e143.

doi pubmed - Davis LE, Koster F, Cawthon A. Neurologic aspects of influenza viruses. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;123:619-645.

doi pubmed - Gu J, Gong E, Zhang B, Zheng J, Gao Z, Zhong Y, Zou W, et al. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med. 2005;202(3):415-424.

doi pubmed - Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, Wang W, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565-574.

doi - Niizuma T, Okumura A, Kinoshita K, Shimizu T. Acute encephalopathy associated with human metapneumovirus infection. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2014;67(3):213-215.

doi pubmed - Bohmwald K, Galvez NMS, Rios M, Kalergis AM. Neurologic alterations due to respiratory virus infections. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:386.

doi pubmed - Sweetman LL, Ng YT, Butler IJ, Bodensteiner JB. Neurologic complications associated with respiratory syncytial virus. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;32(5):307-310.

doi pubmed - Vehapoglu A, Turel O, Uygur Sahin T, Kutlu NO, Iscan A. Clinical Significance of Human Metapneumovirus in Refractory Status Epilepticus and Encephalitis: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2015;2015:131780.

doi pubmed - Li Y, Li H, Fan R, Wen B, Zhang J, Cao X, Wang C, et al. Coronavirus infections in the central nervous system and respiratory tract show distinct features in hospitalized children. Intervirology. 2016;59(3):163-169.

doi pubmed - Lu L, Xiong W, Liu D, Liu J, Yang D, Li N, Mu J, et al. New onset acute symptomatic seizure and risk factors in coronavirus disease 2019: A retrospective multicenter study. Epilepsia. 2020.

doi pubmed - West TW, Hess C, Cree BA. Acute transverse myelitis: demyelinating, inflammatory, and infectious myelopathies. Semin Neurol. 2012;32(2):97-113.

doi pubmed - Coriolani G, Ferranti S, Biasci F, Lotti F, Grosso S. Acute flaccid myelitis temporally associated with rhinovirus infection: just a coincidence? Neurol Sci. 2020;41(2):457-458.

doi pubmed - Colombo I, Forapani E, Spreafico C, Capraro C, Santilli I. Acute myelitis as presentation of a reemerging disease: measles. Neurol Sci. 2018;39(9):1617-1619.

doi pubmed - Xia JB, Zhu J, Hu J, Wang LM, Zhang H. H7N9 influenza A-induced pneumonia associated with acute myelitis in an adult. Intern Med. 2014;53(10):1093-1095.

doi pubmed - Salonen O, Koshkiniemi M, Saari A, Myllyla V, Pyhala R, Airaksinen L, Vaheri A. Myelitis associated with influenza A virus infection. J Neurovirol. 1997;3(1):83-85.

doi pubmed - Nemoto W, Yamagata R, Nakagawasai O, Nakagawa K, Hung WY, Fujita M, Tadano T, et al. Effect of spinal angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activation on the formalin-induced nociceptive response in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;872:172950.

doi pubmed - Ogata Y, Nemoto W, Yamagata R, Nakagawasai O, Shimoyama S, Furukawa T, Ueno S, et al. Anti-hypersensitive effect of angiotensin (1-7) on streptozotocin-induced diabetic neuropathic pain in mice. Eur J Pain. 2019;23(4):739-749.

doi pubmed - McGrogan A, Madle GC, Seaman HE, de Vries CS. The epidemiology of Guillain-Barre syndrome worldwide. A systematic literature review. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;32(2):150-163.

doi pubmed - Fokke C, van den Berg B, Drenthen J, Walgaard C, van Doorn PA, Jacobs BC. Diagnosis of Guillain-Barre syndrome and validation of Brighton criteria. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 1):33-43.

doi pubmed - Yuki N, Hartung HP. Guillain-Barre syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):2294-2304.

doi pubmed - Sedaghat Z, Karimi N. Guillain Barre syndrome associated with COVID-19 infection: A case report. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;76:233-235.

doi pubmed - Kuwabara S. Guillain-Barre syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. Drugs. 2004;64(6):597-610.

doi pubmed - Welge-Lussen A, Wolfensberger M. Olfactory disorders following upper respiratory tract infections. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;63:125-132.

doi pubmed - Bagheri SHR, et al. Coincidence of COVID-19 epidemic and olfactory dysfunction outbreak. medRxiv. 2020.

doi - Sungnak W, et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry genes are most highly expressed in nasal goblet and ciliated cells within human airways. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2020.

doi - Netland J, Meyerholz DK, Moore S, Cassell M, Perlman S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection causes neuronal death in the absence of encephalitis in mice transgenic for human ACE2. J Virol. 2008;82(15):7264-7275.

doi pubmed - Brann D, et al. Non-neural expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the olfactory epithelium suggests mechanisms underlying anosmia in COVID-19 patients. bioRxiv. 2020.

- Giacomelli A, Pezzati L, Conti F, Bernacchia D, Siano M, Oreni L, Rusconi S, et al. Self-reported olfactory and taste disorders in SARS-CoV-2 patients: a cross-sectional study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020.

- Deems DA, Doty RL, Settle RG, Moore-Gillon V, Shaman P, Mester AF, Kimmelman CP, et al. Smell and taste disorders, a study of 750 patients from the University of Pennsylvania Smell and Taste Center. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117(5):519-528.

doi pubmed - Leung TW, Wong KS, Hui AC, To KF, Lai ST, Ng WF, Ng HK. Myopathic changes associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome: a postmortem case series. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(7):1113-1117.

doi pubmed - Tsai LK, Hsieh ST, Chao CC, Chen YC, Lin YH, Chang SC, Chang YC. Neuromuscular disorders in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(11):1669-1673.

doi pubmed - Di Muzio A, Bonetti B, Capasso M, Panzeri L, Pizzigallo E, Rizzuto N, Uncini A. Hepatitis C virus infection and myositis: a virus localization study. Neuromuscul Disord. 2003;13(1):68-71.

doi - Congy F, Hauw JJ, Wang A, Moulias R. Influenzal acute myositis in the elderly. Neurology. 1980;30(8):877-878.

doi pubmed - Dietzman DE, Schaller JG, Ray CG, Reed ME. Acute myositis associated with influenza B infection. Pediatrics. 1976;57(2):255-258.

- Cabello-Verrugio C, Morales MG, Rivera JC, Cabrera D, Simon F. Renin-angiotensin system: an old player with novel functions in skeletal muscle. Med Res Rev. 2015;35(3):437-463.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.